Few public services provoke as much frustration as the state of Britain’s roads. Potholes have become a political shorthand for visible decline – cited by MPs at the despatch box, by councillors on the doorstep and by motorists every time a tyre blows or a suspension fails. Yet when the data is examined in the round, a more uncomfortable truth emerges: the UK’s pothole crisis is not caused by a lack of information about road condition, but by a system that rewards denial rather than prevention.

Three separate bodies of evidence make this clear.

First, there is the UK Pothole Index 2025, published by First Response Finance, which draws on Freedom of Information responses to identify the local authorities with the highest number of potholes recorded between 2022 and 2025. Devon, Surrey, West Sussex, Oxfordshire and Kent top the list, each reporting well over 80,000 potholes over the period.

Second, there is claims data on pothole related vehicle damage, compiled from local authority disclosures and reported by The Times. This shows not only how many claims councils receive, but how many they choose to pay.

Third, there is the Department for Transport (DfT’s) official road condition statistics, used by RAC in its pothole reporting and maps. These classify minor roads into “green”, “amber” and “red” condition, with “red” indicating roads that should be investigated and may require urgent intervention.

Taken together, these datasets paint a stark picture.

Worse roads do not mean fairer outcomes

Intuitively, one might expect councils with the worst roads to be more willing to compensate motorists whose vehicles are damaged. The evidence shows the opposite.

Among the councils topping the UK Pothole Index, claim volumes are extremely high – often running into several thousand per year. Yet payout rates are consistently low. Surrey, Kent and Essex all pay out on fewer than one in ten claims. Devon and West Sussex sit only marginally higher.

By contrast, a small number of authorities – including Shropshire, Highland, Coventry and Wiltshire – pay more than half of all claims they receive, despite not being the worst affected by potholes nationally.

The implication is clear: compensation outcomes are driven far more by internal policy and legal posture than by the condition of the road network itself.

“Red” roads do not protect motorists

The DfT’s road condition data reinforces this conclusion. In theory, roads classed as being in “red” condition represent a formal acknowledgement that the asset is in poor shape. In practice, that classification offers motorists little protection.

Several authorities with a high proportion of minor roads in red condition still reject the overwhelming majority of damage claims. There is no consistent relationship between official recognition of deterioration and a willingness to accept liability.

This undermines a core assumption of the current system: that transparency about road condition leads naturally to accountability. In reality, it does not.

A system that rewards defence over delivery

Why does this gap exist? The answer lies in incentives.

Local authorities are legally able to defend pothole claims by demonstrating that they operate reasonable inspection regimes and repair schedules, even if defects still occur between inspections. As a result, it is often cheaper to invest in documentation, legal processes and claims handling than to accelerate preventative maintenance.

The data shows the consequence of this logic. Authorities with the highest claim volumes frequently have the lowest payout rates. Rejecting claims does not reduce demand; it simply transfers cost and risk onto motorists, while reinforcing a defensive institutional mindset.

This is not a marginal issue. Some councils pay out nothing at all in a given year, despite dozens – or even hundreds – of reported incidents.

Why AI changes the equation

This is where emerging uses of AI matter – not as a technological novelty, but as a mechanism for changing behaviour.

Crucially, AI does not solve a visibility problem. Councils already know where their worst roads are. What AI offers is the ability to move from retrospective reporting to predictive intervention.

AI enabled systems can analyse images, sensor data and deterioration patterns to identify defects earlier, predict which sections of road are most likely to fail, and prioritise repairs before potholes become claims. That shifts the economics decisively. Early intervention is cheaper than reactive patching, and vastly cheaper than the combined cost of vehicle damage, claims administration, legal defence and reputational harm.

More importantly, it reframes accountability. If a council can demonstrate continuous monitoring and proactive repair, the emphasis moves away from whether an inspection regime existed, and towards whether preventable damage was allowed to occur.

| Council | Claims | Percentage Paid | Pothole Index Count (2022–25) | Minor roads in ‘Red’ condition (%) – DfT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shropshire | 2719 | 74.2 | ||

| Highland | 1692 | 70.7 | ||

| Coventry | 280 | 61.4 | 3 | |

| Wiltshire | 3780 | 58.6 | ||

| Stoke-on-Trent | 1474 | 52.6 | ||

| Bury | 666 | 52 | 8 | |

| Flintshire | 639 | 51 | ||

| Middlesbrough | 370 | 50.3 | ||

| Midlothian | 818 | 48.8 | ||

| Dumfries and Galloway | 2650 | 47.7 | ||

| Warwickshire | 1504 | 46 | 4 | |

| East Sussex | 4605 | 45.7 | ||

| National Highways | 5709 | 44.7 | ||

| Newport | 200 | 43 | ||

| Haringey | 96 | 42.7 | ||

| Swindon | 494 | 42.5 | ||

| Cheshire West and Chester | 2703 | 41.6 | ||

| Oldham | 84 | 40.5 | ||

| Wokingham | 238 | 39.5 | ||

| Wigan | 362 | 39 | 2 | |

| South Gloucestershire | 760 | 35.8 | ||

| Barking and Dagenham | 86 | 34.9 | ||

| Bracknell Forest | 241 | 34 | ||

| Kingston upon Hull | 74 | 33.8 | ||

| Oxfordshire | 5388 | 31.8 | 102889 | 8 |

| Brent | 634 | 31.6 | ||

| Bath and North East Somerset | 238 | 30.3 | ||

| Isle of Anglesey | 53 | 30.2 | ||

| Wrexham | 364 | 29.7 | ||

| Cambridgeshire | 4472 | 29.5 | ||

| Gateshead | 218 | 28.9 | 2 | |

| Cumberland | 1991 | 28.4 | ||

| North Lincolnshire | 384 | 27.9 | ||

| Stirling | 328 | 26.5 | ||

| Denbighshire | 394 | 26.4 | ||

| Monmouthshire | 258 | 26.4 | ||

| North Lanarkshire | 599 | 25.4 | ||

| Cardiff | 367 | 24.8 | ||

| Redbridge | 134 | 24.6 | ||

| Scottish Borders | 478 | 24.5 | ||

| Central Bedfordshire | 1685 | 24 | ||

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 358 | 24 | ||

| East Dunbartonshire | 435 | 23.5 | ||

| North Yorkshire | 849 | 23.3 | 3 | |

| Falkirk | 436 | 23.2 | ||

| Bridgend | 140 | 22.9 | ||

| West Sussex | 4975 | 22.6 | 128196 | |

| Luton | 318 | 21.4 | ||

| Renfrewshire | 572 | 21.2 | ||

| Devon | 4593 | 20.6 | 160374 | 10 |

| Sutton | 104 | 20.2 | ||

| Orkney Islands | 5 | 20 | ||

| Thurrock | 76 | 19.7 | ||

| Wakefield | 303 | 19.5 | 3 | |

| Lincolnshire | 6028 | 18.9 | 6 | |

| Inverclyde | 66 | 18.2 | ||

| Nottingham | 519 | 17.9 | ||

| Fife | 542 | 17.9 | ||

| Kingston (London) | 34 | 17.7 | ||

| Tameside | 53 | 17 | 3 | |

| Sandwell | 263 | 16.7 | 2 | |

| Bolsover | 6 | 16.7 | ||

| West Dunbartonshire | 163 | 16.6 | ||

| Greenwich | 110 | 16.4 | ||

| Halton | 37 | 16.2 | ||

| Redcar and Cleveland | 128 | 15.6 | ||

| Richmond and Wandsworth | 39 | 15.4 | ||

| Southwark | 98 | 15.3 | ||

| Bedford | 160 | 14.4 | ||

| Lewisham | 49 | 14.3 | ||

| Aberdeen City | 137 | 13.9 | ||

| Nottinghamshire | 4278 | 13.7 | 4 | |

| Hampshire | 6408 | 13.4 | 4 | |

| Rutland | 130 | 13.1 | ||

| Derby | 146 | 13 | ||

| Milton Keynes | 502 | 12.8 | ||

| Wolverhampton | 462 | 12.6 | 2 | |

| Powys | 376 | 12.5 | ||

| East Renfrewshire | 337 | 12.5 | ||

| Trafford | 489 | 12.3 | 5 | |

| Ealing | 58 | 12.1 | ||

| Enfield | 167 | 12 | ||

| Hertfordshire | 4383 | 11.9 | 4 | |

| Brighton and Hove | 439 | 11.6 | ||

| Vale of Glamorgan | 474 | 11.6 | ||

| Surrey | 6477 | 10.9 | 138159 | 5 |

| Leicestershire | 696 | 10.8 | 4 | |

| Ceredigion | 48 | 10.4 | ||

| West Lothian | 745 | 10.1 | ||

| Perth and Kinross | 524 | 9.7 | ||

| Buckinghamshire | 4395 | 9.4 | 6 | |

| North Tyneside | 266 | 9.4 | ||

| Blackburn with Darwen | 131 | 9.2 | ||

| Bradford | 517 | 8.5 | ||

| Walsall | 94 | 8.5 | 1 | |

| Hillingdon | 173 | 8.1 | ||

| East Ayrshire | 277 | 7.9 | ||

| Caerphilly | 133 | 7.5 | ||

| Kent | 4390 | 7.5 | 85627 | |

| Kirklees | 818 | 7.5 | ||

| Cornwall | 1293 | 7.4 | ||

| Southend-on-Sea | 142 | 7 | ||

| Worcestershire | 602 | 7 | 4 | |

| Sunderland | 190 | 6.8 | 1 | |

| Isle of Wight | 109 | 6.4 | ||

| Telford and Wrekin | 229 | 6.1 | ||

| Torfaen | 116 | 6 | ||

| Leicester | 249 | 6 | ||

| City of Edinburgh | 2389 | 5.9 | ||

| North Ayrshire | 626 | 5.8 | ||

| East Lothian | 213 | 5.6 | ||

| Essex | 5532 | 5.6 | 3 | |

| Medway | 522 | 5.6 | ||

| North East Lincolnshire | 74 | 5.4 | ||

| Blaenau Gwent | 96 | 5.2 | ||

| Torbay | 40 | 5 | ||

| Westminster | 73 | 4.1 | ||

| Waltham Forest | 49 | 4.1 | ||

| South Ayrshire | 281 | 3.9 | ||

| Pembrokeshire | 234 | 3.9 | ||

| Rotherham | 501 | 3.8 | 2 | |

| Blackpool | 108 | 3.7 | ||

| Swansea | 981 | 3.1 | ||

| Warrington | 241 | 2.9 | ||

| Wirral | 81 | 2.5 | ||

| West Northamptonshire | 2637 | 2.1 | ||

| Windsor and Maidenhead | 246 | 2 | ||

| Merthyr Tydfil | 6 | 0 | ||

| Peterborough | 77 | 0 | ||

| City of London | 2 | 0 | ||

| Kensington and Chelsea | 19 | 0 | ||

| Shetland Islands | 2 | 0 |

Sources: The Times, local authority pothole damage claims and payout data; First Response Finance, UK Pothole Index 2025 (pothole counts, 2022–25); Department for Transport, Road conditions in England thttps://ckan.publishing.service.gov.uk/dataset/pothole-enquiries/resource/1ac4e5be-441e-44bc-a09a-99f8adfe4793?inner_span=True&utmo March 2024 (RDC0120 – B and C roads), as referenced in the RAC’s pothole index analysis.

The trust dimension

There is also a wider political consequence. Potholes have become emblematic of a perceived breakdown in the social contract between taxpayers and the state. Motorists see roads deteriorate, claims rejected and responsibility deflected.

AI enabled pothole repair offers a different narrative: one focused on prevention rather than denial. For councils, it provides a route to restore public confidence by demonstrating that problems are fixed before they damage vehicles, not after residents file complaints.

The policy implication

The headline conclusion from the data is uncomfortable but unavoidable. Britain’s pothole crisis persists not because councils lack information, but because the system incentivises them to manage liability rather than eliminate risk.

Technology alone will not solve that. But AI, deployed intelligently, offers a way to realign incentives – making early repair cheaper than rejection, and prevention cheaper than defence.

If policymakers are serious about improving road conditions, the debate must move beyond funding envelopes and towards how maintenance decisions are triggered. The data shows that until incentives change, potholes will remain mapped, measured and monetised – but not meaningfully prevented.

Find out more

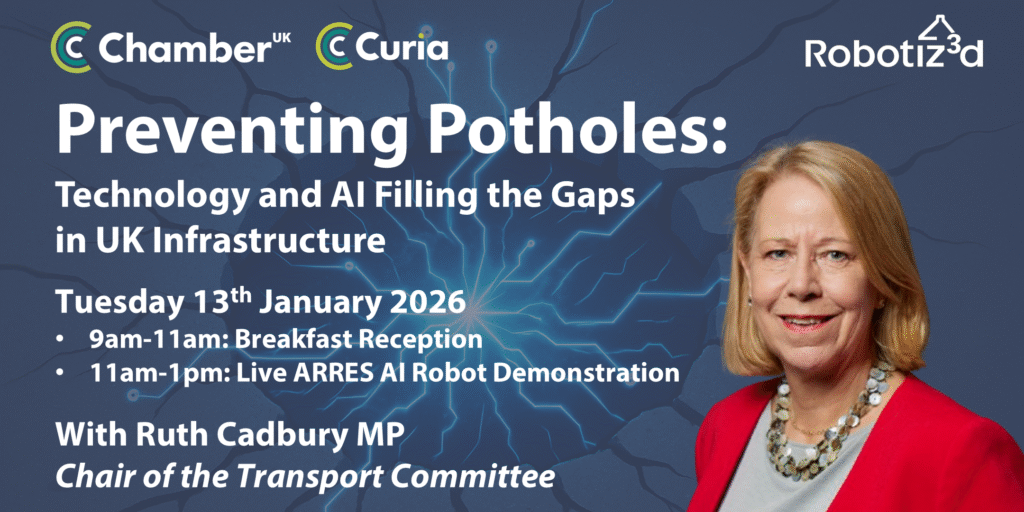

To find out more about Curia’s Housing and Infrastructure Research Group, contact Partnerships Director, Ben McDermott at ben.mcdermott@chamberuk.com

UKAI is also launching the Mobility & Autonomous Systems Working Group which provides a dedicated forum within UKAI for organisations, researchers, and stakeholders working on AI-enabled mobility and autonomous systems.

Its core purpose is to support the development, safe deployment and strategic scaling of autonomous, connected, and robotic systems – including vehicles, freight & logistics, infrastructure robotics, and broader systems relevant to mobility and autonomy – by aligning industry practice, shaping policy and standards, and facilitating cross-sector collaboration. To find out more, contact Membership Director, Stephen Moore at Stephen.Moore@ukai.co