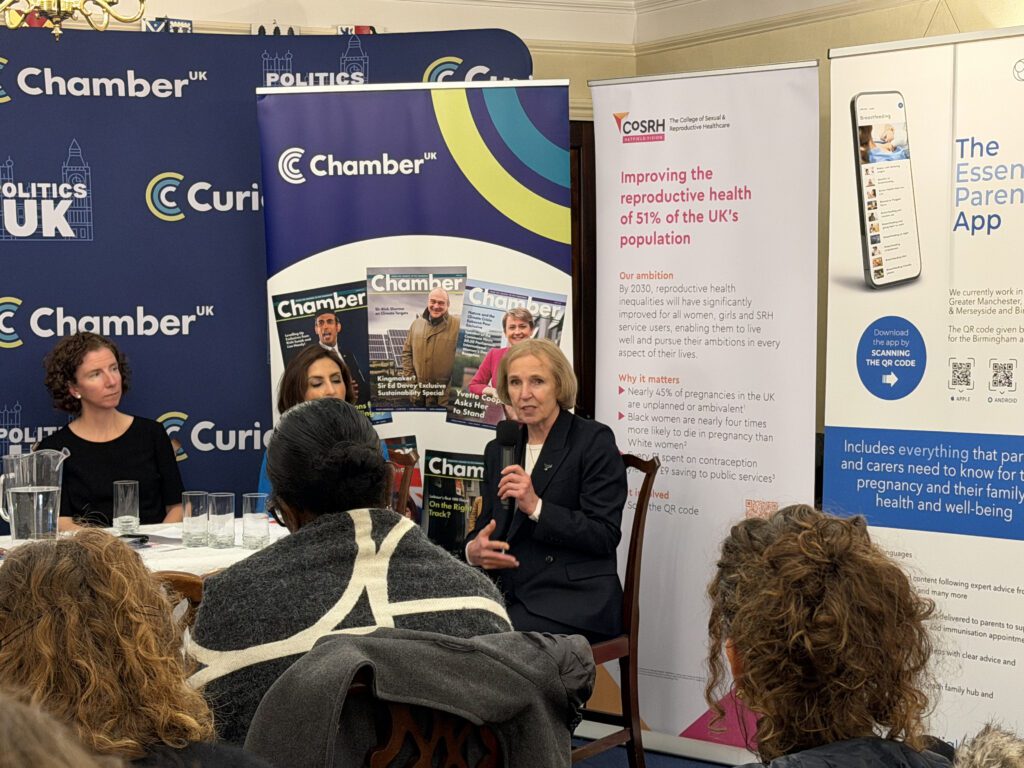

Dame Anneliese Dodds calls for change on women’s health (Photo Left to Right: Dr Zahra Haider, Diana Hill, Dame Anneliese Dodds, Professor Asma Khalil)

For decades, women’s health has been sidelined in policymaking – fragmented across services, under researched and too often dismissed as an individual problem rather than a systemic one.

At a recent Curia panel bringing together parliamentarians, clinicians, researchers, digital innovators and campaigners, the message was unmistakable: women’s health sits at the heart of economic resilience, public service reform, and social justice.

As Paula Sherriff, former MP and founder of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Women’s Health, put it in opening remarks, the challenge is no longer about awareness.

“We know the problems. We know what works. What we need now is delivery – and the political will to make women’s health a core priority rather than an optional extra.”

With women aged 45 to 64 now the fastest growing segment of the UK workforce, the consequences of poor access to care are being felt well beyond individual wellbeing. Workforce exits linked to menopause, long gynaecology waiting lists and unmet reproductive health needs are reducing productivity, increasing pressure on the NHS, and widening inequalities across communities.

Women’s health and the economy: an invisible link

Despite being half the population, women’s health conditions are still routinely treated as marginal. Former Minister of State for Women and Equalities, Dame Anneliese Dodds MP reflected on how recently many issues were simply absent from parliamentary debate.

“There were decades where women’s health was never discussed at all. Even when it was mentioned, it was often trivialised or treated as embarrassing.”

That has begun to change, she argued, with greater recognition of menopause in the workplace, urinary tract infections as a patient safety issue and the need to modernise reproductive health services. But progress remains uneven and vulnerable to political drift.

“Let’s stop saying ‘it’s just’. Normalising women’s pain has normalised failure in the system.”

Rt Hon Dame Anneliese Dodds MP

“What has made the biggest difference has been women telling their stories. The facts matter, but lived experience is what cuts through.”

Dodds urged women not to underestimate the impact of their own voices – locally, professionally, and politically – and warned against normalising poor health.

“Let’s stop saying ‘it’s just’. It’s not just pain, not just heavy bleeding, not just something to endure. It affects women’s ability to work, care, study and participate fully in society.”

Fragmented systems, fragmented care

If awareness has improved, delivery remains hampered by how services are organised. President of the College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, Dr Zahra Haider described a commissioning landscape that actively blocks joined up care.

Sexual and reproductive health services, general practice, and gynaecology are often funded and managed separately, leaving women bounced between services even when the clinical expertise already exists.

“I can have the staff, the skills and the capacity to help a woman the same day – but I am not allowed to because of how services are commissioned.”

The result is long waits, unnecessary referrals and widening inequalities, particularly for women from marginalised backgrounds who find complex systems hardest to navigate.

Dr Haider highlighted post pregnancy contraception as a clear example of missed opportunity. Access after birth, pregnancy loss or termination is patchy despite strong evidence that planned pregnancies improve outcomes for both women and babies.

“This is compassionate care that also makes economic sense. But too often it only happens because clinicians find workarounds rather than because the system supports it.”

Women’s health hubs: making care fit around women

Across the panel, women’s health hubs emerged as a practical way to overcome fragmentation. By bringing together multidisciplinary expertise in community settings, hubs can offer menstrual care, contraception, menopause support, cervical screening, and gynaecology triage through a single front door.

Where they are well established, hubs have reduced gynaecology waiting lists and improved patient experience. But access remains inconsistent, with provision varying sharply by geography.

“Services need to fit around women – not force women to fit around services.”

Susan Murray MP, Liberal Democrat Spokesperson for Scotland

MP for Mid Dunbartonshire and Liberal Democrat spokesperson for Scotland, Susan Murray argued that this patchiness is itself a driver of inequality.

“As long as access depends on where you live, women will keep putting up with symptoms they should not have to tolerate.”

She also stressed the importance of physical space – health and care centres that can host specialist nurses, community organisations, and peer support without prohibitive costs.

“These hubs are not just about medicine. They are about dignity, access and making services usable in real life.”

Digital tools as enablers, not add ons

Digital innovation was another recurring theme, with Co-Founder of Essential Parent, Diana Hill cautioning against assuming all technology is equally helpful.

“Digital support works when it is designed around real needs – not when it is a novelty.”

Essential Parent’s work with NHS trusts, integrated care boards and local authorities shows how multilingual, evidence based digital tools can reduce pressure on frontline staff while improving access for families who might otherwise be excluded.

Hill emphasised the importance of accessibility – including visual content for people with low literacy – and local tailoring so that information reflects real services and pathways.

However, she warned that fragmented procurement and short-term funding make it harder to embed digital support into mainstream care.

“If women’s health is a priority, digital tools should be commissioned as part of core pathways, not treated as optional extras.”

Diana Hill, Co-Founder, Essential Parent

Closing the gender health gap

For Janet Lindsay, Chief Executive of Wellbeing of Women, the urgency lies in addressing a gender health gap that has been allowed to persist for generations.

“Women live longer than men but spend significantly more of their lives in poor health. That should concern anyone serious about prevention, productivity, and equality.”

Conditions such as endometriosis, heavy menstrual bleeding and menopause symptoms remain under recognised, while women report being dismissed when seeking help. Education, Lindsay argued, must start earlier – in schools, workplaces, and communities – so that symptoms are recognised and acted on sooner.

Waiting lists for gynaecology services continue to stretch into years, compounding harm, and frustration.

“By the time many women reach specialist care, their condition has worsened unnecessarily. That is a system failure, not a personal one.”

She also highlighted the role of charities and community organisations in reaching women who face additional barriers, from language to stigma.

From research to real world change

Vice President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Professor Asma Khalil focused on the gap between research evidence and everyday care.

“Evidence without implementation does not change lives.”

Professor Asma Khalil, Vice President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Recent work engaging women directly on research priorities revealed a strong emphasis on access, inclusion, and long-term wellbeing rather than narrow clinical categories.

“We need research that reflects real lives – and systems that actually use that evidence.”

Khalil warned that women remain under represented in clinical trials, leading to poorer understanding of how treatments affect them. She also highlighted stark inequalities in maternal outcomes, with Black women significantly more likely to die during pregnancy or shortly afterwards.

“No single profession can fix this alone. It requires co-ordinated action across policy, public health, and clinical care.”

A political choice

Throughout the evening, speakers returned to a shared conclusion: women’s health outcomes are not inevitable. They are shaped by political choices about funding, commissioning, accountability, and leadership.

Increasing women’s representation in elected office matters, not because women are a single bloc, but because lived experience shapes priorities. As Dodds observed, many of the advances to date have been driven by women prepared to speak openly and persistently.

“Raise your voice. Tell your story. Keep pushing. Change has happened before, and it can happen again.”

Rt Hon Dame Anneliese Dodds MP

As Paula Sherriff closed the discussion, she offered a final challenge.

“The cost of inaction is already being paid – by women, by the NHS and by the economy. The question is whether we finally choose to do something different.”