Political change in the UK is rarely defined by a single decision or event. It tends to emerge gradually, as policies move from announcement to implementation and voters begin to judge outcomes rather than intentions.

That dynamic is what gives 2026 its importance.

The first year of a new government is usually dominated by agenda setting. The second is where trade-offs become visible. In 2026, the Government will face simultaneous pressure from elections, limited fiscal headroom and public services operating under sustained strain.

Decisions taken earlier in the Parliament will start to have practical consequences.

As those pressures converge, political messaging becomes harder to sustain on its own. Claims about direction and values give way to questions about pace, prioritisation, and delivery.

After a difficult 2025, for Labour, this will be the first point at which voters assess performance rather than tone. This means the Government will be unable to maintain the narrative of a terrible inheritance “after 14 years of Conservative Government”.

For opposition parties, it is an opportunity to capitalise on dissatisfaction, but also a test of whether they can present coherent alternatives rather than simply register protest. For voters, 2026 is when expectations formed after the General Election are compared with everyday experience.

If the concerns of Cabinet Ministers like Wes Streeting are to be regarded, politics this year is likely to be shaped less by individual announcements and more by whether public services, household finances and local government feel more stable, unchanged or under increasing pressure.

May elections as the first real verdict

The defining political event of the year will be 7 May 2026, when voters go to the polls across much of the UK. On that day, elections will take place for:

- English local authorities, including all London boroughs

- The Scottish Parliament

- The Senedd in Wales

Taken together, these contests represent the largest nationwide electoral test since the Government entered office.

Worryingly for the Prime Minister, these elections are a proxy judgement on Labour’s early record, regardless of the devolved or local nature of many of the contests. That framing will shape media coverage and political reaction.

Labour enters the elections with several vulnerabilities:

- It is defending a large number of English councils won during the final years of Conservative government

- In Scotland, the party faces a competitive three-way contest where expectations are high but outcomes uncertain

- In Wales, Labour’s long dominance is being tested by Plaid Cymru on the left and Reform UK on the right

Reform UK views 2026 as a breakthrough opportunity, particularly in English local government. That adds unpredictability and raises the possibility of vote splitting, fractured councils and results that are politically harder to interpret.

Strong results would give the Government breathing space. Mixed or poor ones would sharpen scrutiny of strategy, priorities and ultimately leadership.

Leadership questions waiting in the wings

Leadership change is not inevitable in 2026, but it is no longer unthinkable.

For Labour, internal pressure is likely to crystallise around three questions:

- Does the Government’s message resonate outside Westminster

- Is enough being delivered quickly enough to justify difficult trade offs

- Can backbench unity be maintained as fiscal choices become clearer?

Disappointing election results could prompt a reassessment of positioning on issues such as migration, crime, and public service reform.

That does not mean an immediate leadership challenge, but it does mean a noisier internal debate.

On the Conservative side, 2026 is widely seen as a make-or-break year for party coherence. Senior figures believe the party must either stabilise under Kemi Badenoch or accept a longer period of fragmentation, particularly if Reform UK continues to pull voters and activists away.

Leadership politics may be an undertone early in the year, but by the summer they could become a constant noise.

Governing under fiscal constraint

Economically, 2026 is likely to be defined by limitation rather than largesse. The room for dramatic fiscal manoeuvre by the Chancellor is narrow, and that reality will shape both policy and politics.

The Financial Times has repeatedly noted that governments operating under tight spending constraints struggle to demonstrate visible progress, even when making technically sound decisions. That dynamic will be central to the year ahead.

Key fiscal issues to watch include:

- Continued reliance on frozen income tax thresholds and fiscal drag

- Public sector pay negotiations, particularly in health and education

- The resilience of capital investment plans during spending reviews

Whether the Chancellor learns something from one of the most communicated Budgets in history, or not, the Spring Statement and the later Budget in 2026 will undoubtedly deliver headlines.

The Government will be judged on whether their announcements feel credible, coherent, and fair. More u-turns like farmers inheritance tax will cause mounting anger from the backbenches. With continued impotence on welfare reform, the danger for the Government is not that it makes unpopular decisions, but that it appears unable to make choices at all.

The politics of restraint is unforgiving. It rewards clarity and punishes drift.

Healthcare as the ultimate test of competence

If there is one policy area that will define political debate in 2026, it is healthcare.

The Government’s 10 Year Health Plan for England sets out an ambitious shift towards prevention, community-based care, and digital services. The challenge is that voters experience the NHS not through strategy documents but through waiting times, access, and staff morale.

With waiting lists on the rise, and continued strike action, the latest NHS activity tracker from NHS Providers suggests that Wes Streeting will find it harder to meet the Government’s pledge to cut waiting times. A challenging backdrop to his leadership prospects.

Analysis from the King’s Fund suggests that 2026 to 2027 is the period when Integrated Care Boards are expected to demonstrate tangible improvement rather than structural change alone. That creates political exposure across several fronts:

- Persistently high waiting lists, particularly in urgent and diagnostic care

- Workforce shortages affecting retention, morale, and continuity of care

- Uneven rollout of community-based models such as Hospital at Home

There is growing political sensitivity around access to care, vaccination uptake, and child health outcomes. These issues cut across ideology and resonate directly with voters’ daily lives.

Healthcare performance will shape perceptions of government competence more powerfully than almost any other factor in 2026. Progress does not need to be dramatic, but it does need to be felt.

Devolution and diverging political pressures

The devolved elections in Scotland and Wales will underline how differently politics is playing out across the UK.

In Scotland, the campaign is expected to focus on:

- NHS performance and waiting times

- Education standards and attainment gaps

- Economic delivery and confidence in government

In Scotland, the SNP has turned itself around in a short timescale – it is now predicted to hold onto Holyrood in a dramatic turnaround of fortunes. However, with NHS waiting lists in Scotland on the rise – their ability to deliver is still under scrutiny.

In Wales, health and social care integration reforms will be under scrutiny, with opposition parties arguing that ambition has not been matched by resources or outcomes.

These contests matter beyond their immediate results. They will shape how much political space the UK Government has to pursue England focused reform without provoking territorial tension or accusations of neglect.

A poor performance in devolved elections would complicate the Government’s wider reform agenda.

Fragmentation as the new political backdrop

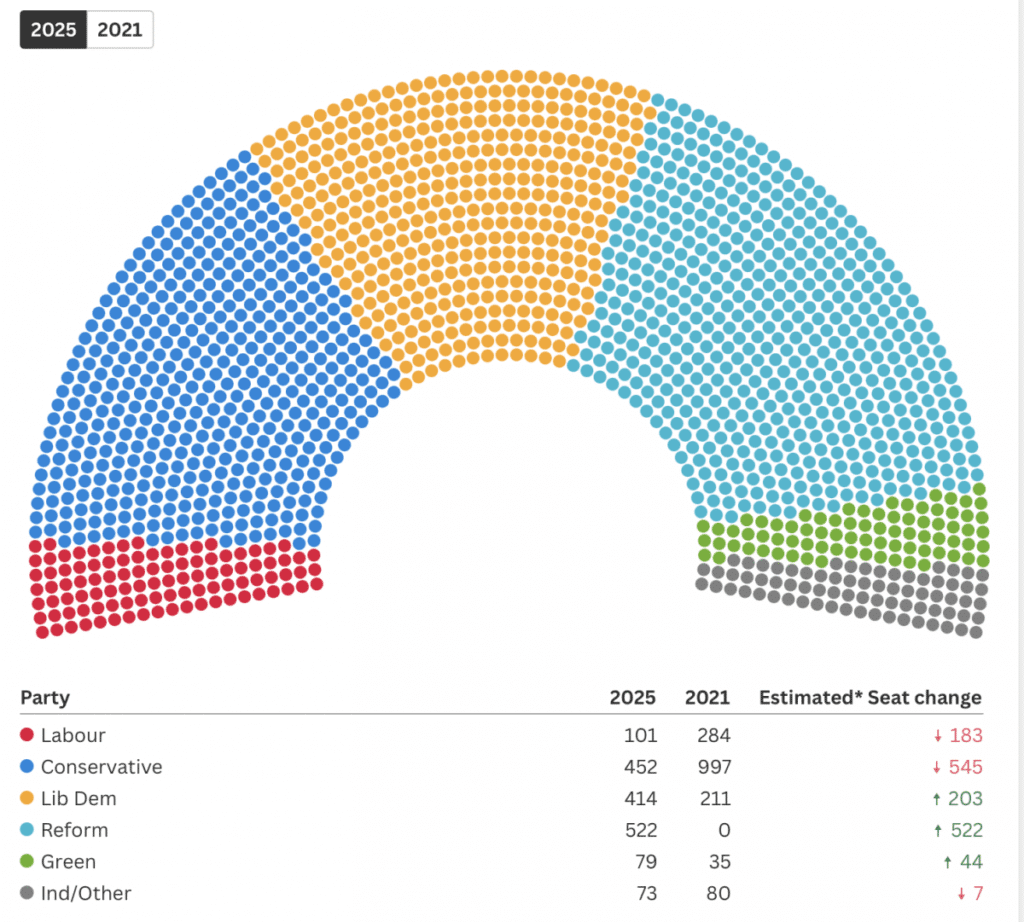

One of the defining features of 2026 is likely to be political fragmentation.

Polling and analysis cited by the New Statesman and Electoral Calculus suggest that multi-party competition is becoming normal rather than exceptional. That changes how elections are fought and how results are interpreted.

This fragmentation is likely to produce:

- More councils under no overall control

- Increased tactical voting and shifting alliances

- Greater influence for smaller parties in local government

- Continued voice for Reform UK and the Greens

For national leaders, this makes message discipline and delivery more important. In a fragmented system, credibility becomes a scarce resource.

What to watch as 2026 unfolds

By the end of the year, several questions should have clearer answers:

- Has Labour established a governing rhythm that survives electoral pressure

- Can the Conservatives rebuild coherence or does fragmentation deepen

- Does NHS reform begin to feel tangible to patients and staff

- Are voters more confident or more sceptical than they were in 2024

2026 will not decide the next General Election but it will determine the terrain on which it is fought. For the Government, it is a year of exposure. For the opposition parties, a year of opportunity.

Above all, it is the year when British politics moves from promises to delivery.

(Image: UK Parliament)