The recent European Movement report launch marks a critical turning point for energy, climate, and environmental co-operation. With both sides pledging ambitious goals, the real challenge lies not in aligning intentions but in accelerating action, overcoming divergence, and safeguarding environmental commitments against political headwinds.

A Window Reopened

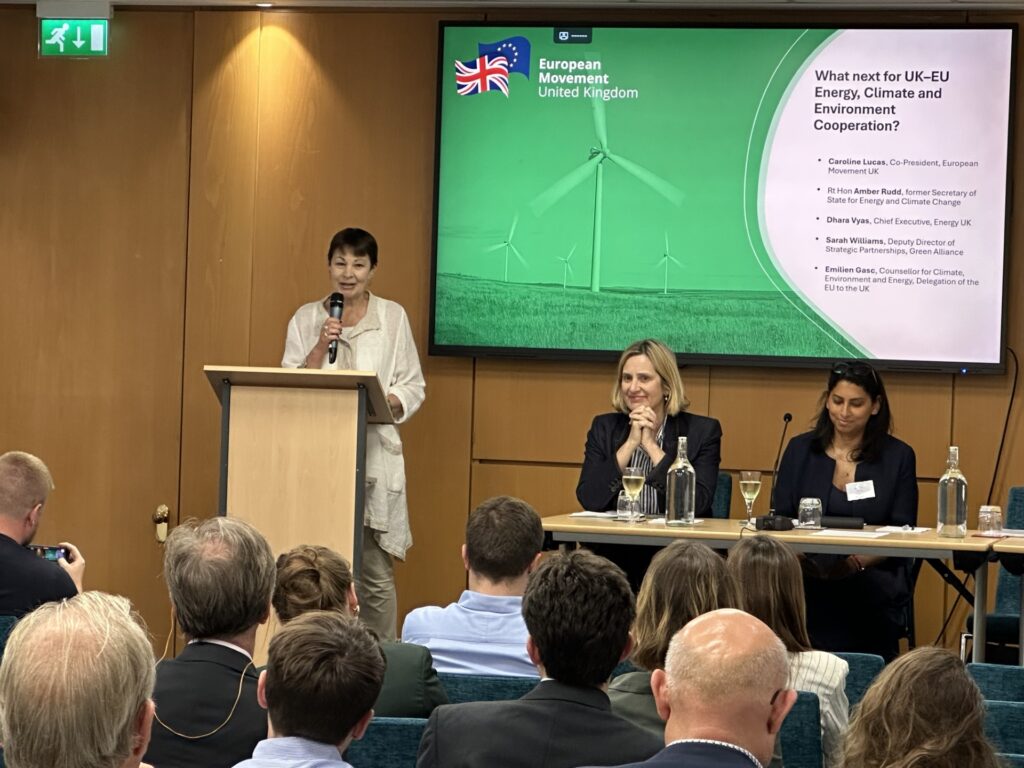

For Lucas, the meeting with UK and EU speakers represented “a long-overdue turning point in our relationship with our closest neighbours.” Years of uncertainty and political drift, intensified by the shadow of Brexit, have stunted the UK’s ability to act collectively with Europe on the most pressing issues of the 21st century: climate change, planetary health, and securing reliable, affordable energy.

“We now have a window,” Lucas said. It is a window to rebuild trust and practical co-operation, and to “rebuild co-operation on the defining challenges of our time: the climate crisis, environmental breakdown, and energy security.”

Her words resonated with policymakers who have struggled to bridge, in practice, the gap between mutual recognition of threats and the delivery of real-world solutions.

Common Goals, Divergent Paths

On paper, the UK and the EU have set an impressive course:

• UK Ambition: Britain has pledged to become a “clean energy superpower,” targeting a fully decarbonised electricity system by 2030. This is a cornerstone commitment in asserting post-Brexit leadership and credibility on the world stage.

• EU Ambition: The European Commission has launched its own clean industrial deal, intent on giving Europe a global competitive edge through green innovation.

“Both the UK and the EU have made this a political priority,” Lucas emphasised. The harmony of aspiration, however, obscures growing dissonance in delivery.

“Ambitions are aligned, delivery is lagging,” she noted, which is not a problem unique to Britain. Across Europe, economic headwinds and political volatility threaten to erode the resolve to push through costly and often unpopular reforms.

Political Headwinds

Behind these lagging efforts is a less visible, but mounting, pressure from those who argue for rolling back or softening environmental policies. In both Brussels and Westminster, parties and stakeholders have questioned the pace – and sometimes the wisdom – of costly decarbonisation, especially as the broader public faces rising living costs.

“There are those advocating for a retreat from strong environmental policy,” Lucas warned.

Policymakers must reckon with this challenge. As climate impacts become more dramatic – from record temperatures to volatile energy prices – the pressure to build a more resilient, integrated approach grows.

The New Question: Not If, But How and How Fast

Former Energy Secretary, Amber Rudd pivoted the debate away from the exhausted binary of “to co-operate or not” and toward a new imperative: “The real question,” she argued, “is not whether we work together, but how – and how fast.”

To policymakers, this is a powerful call to action. International experience increasingly demonstrates that narrow go-it-alone strategies in the face of global crises are insufficient, costly, and self-defeating.

Counting the Costs of Leaving

Here the consequences of Brexit become starkly apparent. Rudd pointedly argued that the UK, having left the EU, “has increasingly found itself on the outside looking in – excluded from vital networks, diverging on standards, and facing higher costs.”

This exclusion is not abstract for the energy sector and green industries:

• Lost Access: The UK no longer participates in specialised cross-border infrastructures and information-sharing arrangements that once allowed for smoother, cheaper energy flows.

• Regulatory Divergence: As British and European standards separate, businesses face growing compliance costs, competitive disadvantages and uncertainty.

• Consumer Impact: These inefficiencies translate directly into higher energy costs and lower resilience for British households and the wider economy.

“The reality is that our continent’s energy needs, and climate vulnerabilities are deeply interdependent,” Lucas reminded the audience. “Fragmentation helps no one.”

What Does This Mean for UK Policymakers and Business?

- Reconnect and Rebuild Practical Links

There is a strong case for seeking re-entry – formally or informally – into key energy and environmental networks previously shared with the EU. Restoring shared platforms for technical dialogue and crisis management will help keep costs in check and innovation flowing. - Guard Against Policy Slippage

Any backsliding on environmental targets, whether for short-term economic relief or political expediency, risks ceding domestic and international credibility. Success will require cross-party resolve and continued engagement with the public and industry. - Accelerate Joint Delivery

The pace of climate and energy transition must accelerate markedly. While ambition is welcome, tangible deliverables in areas such as grid interconnection, renewables deployment, workforce training, and joint R&D will determine credibility. - Position for Global Competition

Both the UK and EU must remember that their ability to compete with North America and Asia on low-carbon industry and innovation depends on the scale and certainty that only collaboration can offer.

Don’t Let the Window Close

Closing her remarks, Lucas voiced a sentiment that finds rare consensus across party and sectoral lines: “We cannot afford to lose momentum now.” The window for UK–EU cooperation on energy and environment has reopened, but history shows such windows do not stay open indefinitely.

If government, business, and civil society seize the moment, the benefits – economic, environmental, and geopolitical – are immense. If not, the UK risks finding itself increasingly marginalised, burdened by higher costs and missed opportunities.

The message from the report is clear: now is the time for focused, accelerated partnership. The only question is whether our politics can keep up with our planet’s needs.

For further insights and policy recommendations, the Curia Clean Energy and Environment Research Group will provide continued analysis as the UK–EU relationship evolves.