If the purpose of Rachel Reeves’ pre-Budget address this morning was to silence mounting speculation about tax rises, it failed.

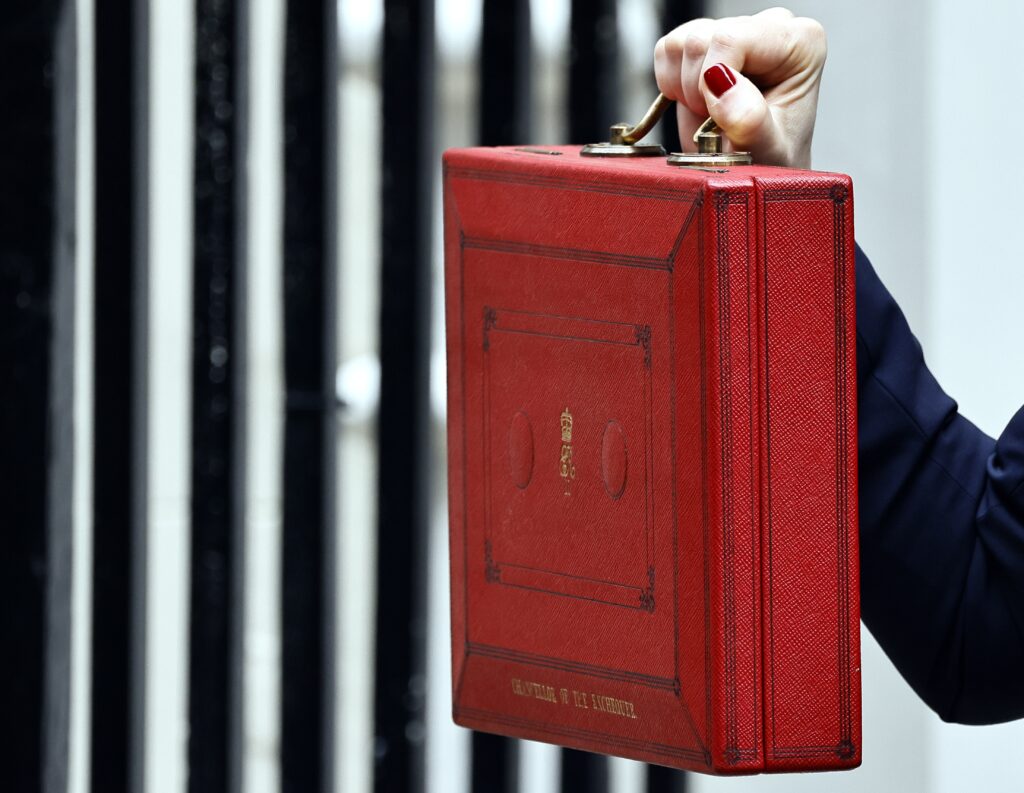

Standing behind the slogan “Strong Foundations, Secure Future” in Downing Street, the Chancellor sought to project calm control ahead of her second Budget. Instead, she delivered the clearest signal yet that Labour is preparing to break its manifesto commitment not to raise income tax, VAT, or National Insurance.

The speech was an unusual move in itself. Chancellors rarely deliver major addresses from Downing Street so close to a Budget. But this was not an economic update – it was political choreography. Reeves’ intent was to start softening up the public, investors, and her own MPs for difficult choices ahead. Yet the message that emerged was not reassurance, but inevitability: higher taxes are coming.

A calculated prelude

Reeves opened by declaring that she would make “the choices necessary to deliver strong foundations for the economy,” stressing the need to bring down national debt and the cost of living. Her tone was careful, measured, and deliberately unspecific. The repeated references to fiscal responsibility and “iron-clad” rules betrayed a Chancellor more concerned with credibility in the bond markets than comfort in the backbenches.

Her argument rested on two pillars. First, that the UK’s fiscal position is worse than previously understood, with national debt at £2.6 trillion – or 94 per cent of national income – and £1 in every £10 of taxpayers’ money now going on debt interest. Second, that global and domestic shocks have squeezed her room for manoeuvre: sluggish productivity, higher borrowing costs, rising defence pressures, and stubborn inflation. These, she argued, are not the result of her own mismanagement, but the legacy of Conservative rule and an “ill-conceived Brexit.”

In short, Reeves’ message was that she has been left to clean up the mess – and that cleaning up costs money.

“The message that emerged was not reassurance, but inevitability: higher taxes are coming”.

Managing expectations – or breaking promises?

Labour’s election manifesto promised not to raise the main rates of income tax, National Insurance, or VAT. Reeves reaffirmed those pledges as recently as September. But this morning, she pointedly did not repeat them. Nor did she rule out rises when pressed by journalists afterwards.

Instead, she invoked the need to make “necessary choices,” to “fund our public services sustainably,” and to “protect the economy from a return to austerity.” Those phrases, repeated throughout, were the linguistic equivalent of white smoke drifting from No. 11 – the early signal of a decision already made.

The challenge for Reeves is that the rationale she outlined today – a worsening £22 billion fiscal gap, a productivity downgrade from the Office for Budget Responsibility, and the costs of international instability – reads less like an explanation and more like a pre-emptive justification. If the Government was elected on a promise to end the “cycle of decline,” today’s message was that decline is proving more expensive to end than expected.

The framing of necessity

Reeves’ political strategy is clear: recast any tax rises not as broken promises, but as acts of national responsibility. “Politicians who offer easy answers are irresponsible,” she said pointedly – a line aimed as much at her Conservative predecessors as at her own critics. Yet the phrase also neatly anticipates the charge of betrayal. By presenting tax rises as “necessary,” Reeves is seeking to move the argument from morality to mathematics.

The problem is that voters may not see it that way. Labour’s landslide victory was built on trust – the promise that a Labour Government would deliver change without shock. Many voters who turned from the Conservatives to Labour did so on the understanding that their own taxes would not rise. If Reeves does lift the basic or higher rate, even marginally, it will be politically costly, however carefully she frames it.

The economic reality behind the rhetoric

Economically, Reeves is correct to say that the fiscal picture is tightening. The OBR’s expected downgrade in productivity forecasts could add up to £20 billion to her fiscal challenge, and the Chancellor’s own rules – to have debt falling as a share of GDP by the end of the Parliament, and not to borrow for day-to-day spending – sharply constrain her options.

The question, then, is not whether Reeves will raise revenue, but how. The Resolution Foundation has suggested that a modest income tax rise, offset by a cut in National Insurance, could raise £6 billion while limiting pain for most workers. Others have proposed extending the freeze in tax thresholds to 2030, a stealthier but equally costly option for households. Each of these measures would test Labour’s promise not to raise taxes on “working people.”

The Chancellor could instead target capital gains, inheritance, or wealth taxes – measures more aligned with Labour’s political instincts – but these yield less and come with complex behavioural effects. As Reeves herself noted, there are “limits to how much government can borrow.” The implication is unavoidable: the largest levers are those Labour pledged not to touch.

A controlled performance, but a risky act

Reeves projected seriousness, consistency, and fiscal prudence – qualities designed to reassure financial markets and middle-ground voters. But beneath the polish lay the beginnings of a difficult few weeks politically.

This was, as one commentator put it, “the first third of the Budget speech” delivered three weeks early: an exercise in expectation management. Yet if her aim was to dampen speculation, the effect was the opposite. Every line about “necessary choices” or “sustainability” has only fuelled the sense that major tax rises are now inevitable.

The Chancellor may hope that by framing her decisions in advance, she can control the narrative when the Budget is delivered. But politics rarely allows such neat sequencing. By stepping out early, Reeves has invited scrutiny of not only the scale of the fiscal hole but the credibility of the promises Labour made to fill it.

A test of trust

For now, the Chancellor’s message is that Labour remains a party of growth and fairness, capable of restoring economic stability without returning to austerity. Yet in choosing to highlight the constraints rather than the opportunities, Reeves risks cementing a perception that Labour’s ambitions are already being hemmed in by fiscal orthodoxy.

Her speech was meant to build confidence ahead of the Budget. Instead, it has raised the stakes. If, on 26 November, Reeves announces the very tax rises she spent months insisting would not happen, the question will not simply be whether they are economically necessary – but whether the Government can maintain the political trust that made them possible in the first place.