The British Spirit and the Art of the Debacle

When the Titanic sank on a bitter April night in 1912, her captain, Edward J. Smith’s reported last words were: “Be British.” We can infer with confidence that the late captain was referring to the bravery and dogged, reckless pneuma which defines our national spirit rather than some gesticulated nod to crass stereotypes. The British are unique in this impetuous hauteur. The Germans have efficiency and roboticism and the French have style, but the British are more dogged, brave, resolute and tenacious than either of them. They are steadfast in the face of utter disaster, as exemplified by our mighty symbols of national folklore – the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Titanic and Dunkirk. No nation fails more magnificently and shamelessly, yet with such hubris. While fighting in the Falklands War, Prince Andrew described being shot at as “very character building”. Perhaps in the light of subsequent events he ought to have been shot at a little more.

A week prior, the most popular politician in the country made a fleeting bid to stand as an MP in the Gorton and Denton by-election, in the nick of time before the 5pm deadline only to be blocked by the National Executive Committee (NEC) a day later. Perhaps Starmer and his allies were taking a leaf out of the late captain’s book, taking on the form of passengers on the Titanic, steadfastly refusing to man the lifeboats out of loyalty to a failing strategy; simultaneously doing so in utterly shameless fashion in full view of a public furiously shaking their heads.

The Cynical Game of Westminster

The response to this could have almost been guessed verbatim. This is a uniform trait amongst the Westminster contingent, for MPs are an almost lab-designed, meticulously crafted class of people (often literally choreographed in the same elite educational institutions and Old Boys’ Clubs). Should they be asked to comment on the scandal regarding the use of their tax-funded expenses to pay for lampshades or slotted cutlery from Marks & Spencer, they’ll be quick to remind the public that there are far greater matters to attend to such as the cost of living crisis or the war in Ukraine. Like clockwork, Starmer offered much of the same response when asked to justify this, stating: “Having an election for the Mayor of Manchester when it’s not necessary would divert our resources away from the elections that we must have.” If there was ever an instance which lends truth to the quote by Slavoj Žižek that “in contemporary societies… cynical distance, laughter, irony, are, so to speak, part of the game. The ruling ideology is not meant to be taken seriously or literally” then it is here where the NEC’s decision is hegemonic as this is not a charade lost on the people of Manchester. In a recent poll by the New Statesman, just 7% of people agree with the NEC’s stated reason that a mayoral by-election would be an expensive inconvenience for locals and 33% even say the party blocking Burnham would make them “less likely” to vote Labour.

Touching Down in the “Echo Chamber”

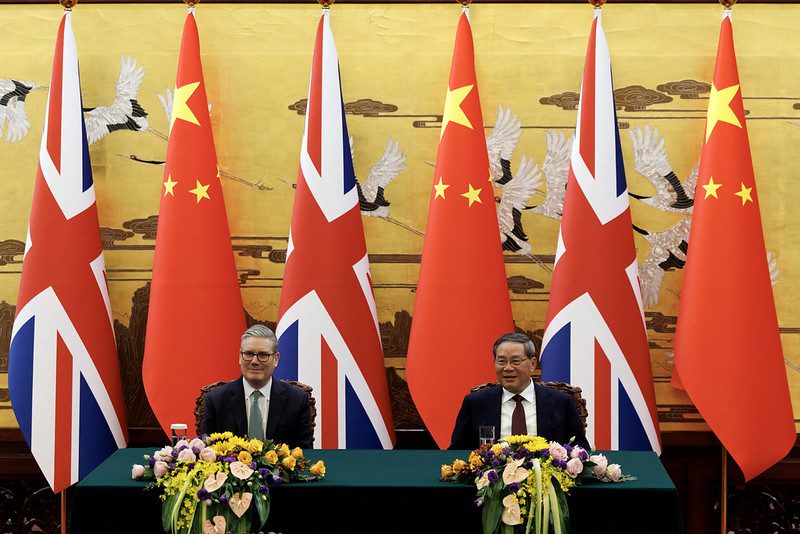

And so Starmer’s gleeful announcement on X that he had “touched down” in China was met with the expected hostility by the suspiciously uniform horde of Union Jack-draped bulldog profile pictures on X iterating word salad lambasts reminiscent of a McCarthyist Red Scare era. In the eyes of the cesspit of Musk’s echo chamber, Starmer is somehow in the cross section of Thatcher’s imago Dei and also Lenin’s love child, ready to open the door to the looming spectre of socialism whilst simultaneously somehow enacting soft austerity with all the coiffured virility of Mrs T herself.

Image: Prime Minister Keir Starmer visits Yuyuan Garden in China – No 10 Downing Street / Simon Dawson

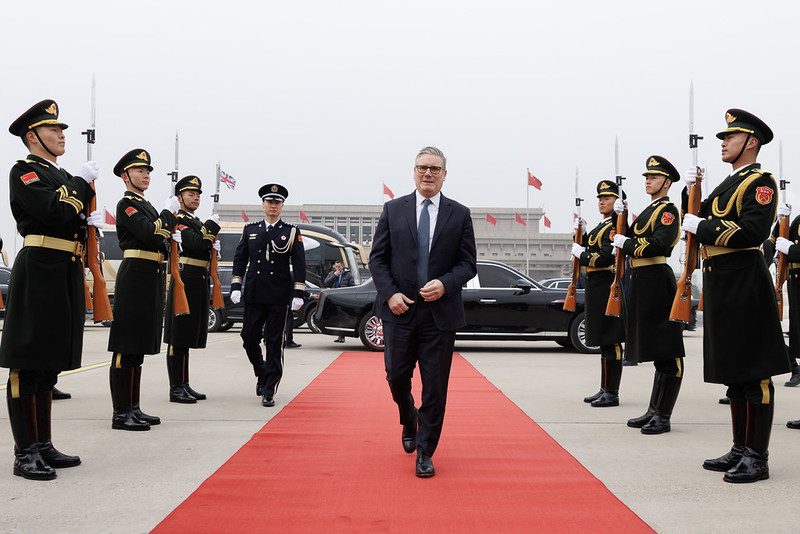

In a video which beamed into the timelines of Britons nationwide of the Prime Minister being led through a bellicose convoy of discernibly tall armed guards – whom we can assuredly assume were purposefully selected – you can almost, for a second, see the enormity of the situation dawning upon this former human rights lawyer, son of humble parents; the real-time realisation that he’s a long way from home, a long way away from swanky London middle-class dinner parties. Facing the grandeur of an authoritarian hegemon in a bid to secure trade, Starmer, in the eyes of many, is out of his depth. Yet there is a newfound glimmer of reappraisal for our head of government in this controversial spectacle; just weeks after having to fend off the underhand threat of a de-facto leadership challenge in the face of plummeting approval ratings, our party leader faces down the autocratic custodian in a bid to revitalise a frayed labour market and reassert our nation’s status on the global podium. He may not have the nation on his side, yet still, he’s there. What is a debacle to many could just as easily be interpreted to be a leader still swinging in the eleventh round to remind the world that Britain is not a joke.

Souvenirs from a Transnational Holiday

The aim – he stated – was to “deliver for the British people”, and more specifically, “securing trade” was the designated motive for this obscure visit – the first British Prime Minister to meet the controversial figure since 2018. When David Cameron welcomed him in 2015, he did so with the warm quintessential embrace of British culture – drinking pints in a pub named ‘The Plough’ whilst donning a red Poppy on the lapel and taking him to watch a Manchester City match, yet still utterly unable to shake the Etonian-Oxford graduate pneuma upon which he was immaculately clad in. Starmer is set to bring home some souvenirs from his trans-national holiday (no, not a t-shirt that says “I heart China”) – free visa travel for Brits wanting to stay in China below 30 days as well as announcing a border security agreement with China to crack down on the flow of Chinese-made small boat parts after 60% of small boat engines used by migrants were found to be Chinese-manufactured. Billions sealed in export deals and expanded market access for UK firms, job creation in Port Talbot and inward investment with Chinese firms creating hubs in London and Liverpool. Yet, this shouldn’t be the only thing he brings home from his visit.

The Industrial Blueprint

Over the past four decades, the Chinese state has systematically built an integrated manufacturing ecosystem, combining large-scale infrastructure investment, state-backed finance, regional industrial clusters and an abundant, increasingly skilled labour force. The result is sustained productivity growth, high investment coupled with technological upgrading. Britain, however, has done the opposite: it has relied on fragmented private investment, dismantled domestic supply chains, allowed manufacturing to collapse and attempted to replace industry with services and finance in a new age of managerial corporatism, endless e-mail jobs and ushering in the age of the “knowledge economy” after a four decade long sustained bludgeoning of its industrial hubs and deregulated labour market. The result has been catastrophic, for a community to not only suffer the material damage of deindustrialisation but experience the deracination of the bonds and dignity of labour which once rested upon the hands that wove it.

Image: Prime Minister Keir Starmer walks on the Bund in Shanghai – No 10 Downing Street / Simon Dawson

This is, of course, not a treatise on how Britain should adopt an authoritarian regime with Chinese characteristics and for Brits to refer to the Prime Minister as ‘Chairman Keir’, but that the lesson learnt from our visit ought to be that it needs ambition backed by institutional power. Without a state capable of building industries, the heralded ‘green transition’ will remain a conveniently easy-to-reach-for titbit of rhetoric rather than an economic reality. Labour’s tragedy is that it recognises the necessity of transformation yet lacks the courage to pursue it.

Blueprints vs Livelihoods

The machinery of decarbonisation exists in blueprints and acronyms – GB Energy, the National Wealth Fund, the Industrial Strategy Council, but not yet in the livelihoods of workers across the North and Midlands where Labour’s green transition has so far struggled to match its own rhetoric. The manifesto’s promise of 650,000 new green jobs has yet to materialise over a year into government, even as traditional industrial decline deepens. When the Titanic sank in 1912, Belfast ship builders defended their industrial pride with all of the admirable parochial hubris in: “She was fine when she left here!”. Samson and Goliath still stand tall over Belfast’s skyline as a potent symbol of industrial virility in a sector which has been beset with decline since WW2. Yet Harland & Wolff, forever burdened as the architects of the tragic vessel and, for many, a symbol of sectarian discrimination, now limps along under a rescue deal with a Spanish state company. Port Talbot and Scunthorpe steelworks face layoffs as they move to greener electric furnaces; Grangemouth refinery has been shuttered and repurposed as an import terminal by its Chinese owner. Britain’s industrial affairs, so to speak, are a sorry sight. But what is Labour doing about it?

The Problem with Skills-Based Policy

Beyond the job growth stimulus in the green sector, Labour have invested in a plethora of skills programmes in a welfare-to-work bid; Skills England is a national body to coordinate apprenticeships and further education as well as adult retraining. The caveat, however, is this is a corrective measure in a crumbling labour market which has evidenced its inability to align the demand-side crisis in a deregulated economy. Labour has also pledged to reform the Apprenticeship Levy to make it easier for SMEs to use funds and expand technical apprenticeships specifically in green energy. This, of course, relies on employers; if firms refuse to expand with no industrial incentive to do so, these apprenticeships do not scale. Perhaps most saliently, the party’s “just transition” coupled with its lamenting promise that “no community is left behind” with its redeployment of carbon-intensive workers… Yet as it remains, there exists virtually zero large-scale redeployment mechanism – and the Unions haven’t missed this. Sharon Graham, leader of Unite the Union, said: “We know what’s said about the jobs… But where are they?… We’ve been promised 650,000 in these new, green industries… But show me them. I can’t see them. Is someone driving an electric delivery bike working in a green industry of the future?”.

Image: Prime Minister Keir Starmer is given a guard of honour as he leaves Beijing – No 10 Downing Street / Simon Dawson

If Starmer wants to give Sharon Graham a witty answer to this, perhaps he should look towards the man he has spent the last few days with. Where a skills-based policy approach in Britain is treated as a substitute for industrial policy rather than its complement, China does the opposite. It builds industries first through state-backed investment, infrastructure and regional industrial planning, and only then scales vocational training to meet the labour demand those industries generate. The result is that China produces engineers for factories that exist, while Britain trains workers for jobs that often do not. It’s no use me trying to eat soup with a knife and fork or play the tuba with no fingers, in a similar fashion that it’s no use trying to run a developmental industrial strategy with neoliberal tools. This is partially why Labour candidates who once slept soundly on election night in the former-industrial red wall may worry about getting their deposit back in 2029.

The Legacy of Deng Xiaoping

None of this developmental strategy in China was an accident. In the decades following Mao’s death, and particularly after the ascension of Deng Xiaoping in the 1960s and 70s, the Chinese state turned their attention towards an export-oriented growth strategy that was neither socialist orthodoxy nor unfettered capitalism. If Deng was not a Marxist in theory, he was certainly one in outlook in the way he argued for the forces of production to be unleashed to ascend to a higher level of output for the benefit of the state’s labour force. If Marx requested a carrier of the flame in his insistence that redistribution could not exist in a period of stagnation, then it’s arguable that Deng was the one who stepped up. Foreign capital was welcomed however with the salient caveat that Chinese labour was injected into global supply chains with ruthless efficiency. Britain now struggles, even four decades on, to cling onto the wreckage of Thatcher’s grand experiment when it surrendered state control of the economy and sold off the cash cow of sovereign wealth funds. Where Britain was sowing the seeds of privatisation, China was reaping the rewards of its meticulous state planning and the ship of deindustrialisation was docking in the harbour.

Selling into China, Not Rebuilding Britain

Ultimately, our prime minister brings home £2.2bn in export deals and around £2.3bn in market access over 5 years; for a country utterly bereft of a beneficial growth model, this is paramount. Cultech will export up to £90 million over five years through a partnership with China Resources, creating 55 jobs in Port Talbot where it previously saw layoffs; Silverstream Technologies projects over £50 million in exports to 13 Chinese shipyards in 2025; Anemoi Marine Technologies will generate £28 million from Flettner Rotor Sail installations; and Brompton Bikes anticipates £111.5 million in Chinese sales over three years. A cynic, however, might raise the point that these deals are firm-level, revenue-driven and exist solely to generate revenue. Thus, Starmer’s exotic visit has been far from a failure, but similarly not a ‘win for the parish’. Cracks in Britain’s economic strategy are still there for all to see – job creation in niche sectors which will exist without regional clusters or skills pipelines necessary for large-scale industrial renewal. In effect, Britain is selling into China without rebuilding anything resembling a domestic industrial base.

Featured Image via No 10 Downing Street / Lauren Hurley