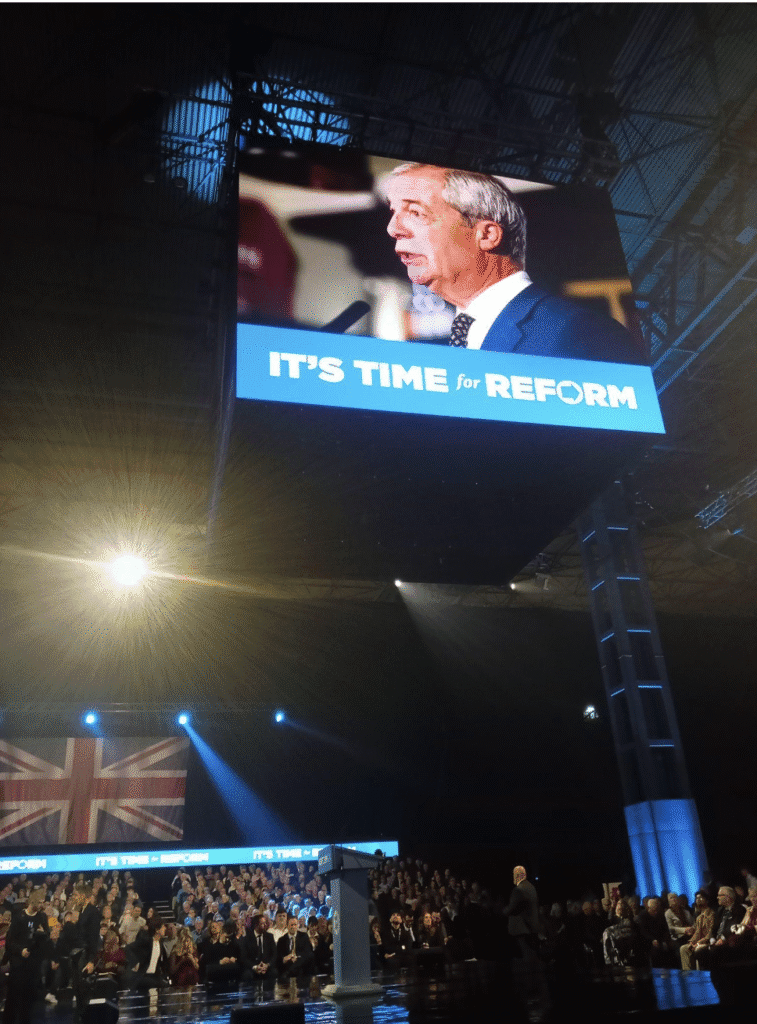

Populism is back, with pyrotechnics and t-shirt cannons attached. On the 9th February, Reform UK held its “Time for Reform” rally at the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) in Birmingham, in an attempt to bring together party members, activists and its parliamentary team to supposedly get ready to fight a general election.

Unfortunately for Nigel Farage, the odds of a general election happening soon are close to none, since Keir Starmer managed to fight his way back from the edge of resignation, after support from his parliamentary party.

The Rally made clear early on that this was not intended to be a conventional political event. Jeremy Kyle, acting as Master of Ceremonies, opened proceedings by gesturing towards the press seats and remarking “Oh, there’s the press. There they are,” before adding, “Don’t fall up the stairs, idiot.” This rhetoric mimics Donald Trump’s attacks on the so-called “fake media”, albeit without any of Trump’s likability.

Richard Tice

Richard Tice was introduced first, positioned as Reform’s managerial antidote to political failure. He framed the Party’s rise as an “entrepreneurial political start-up”, claiming Reform had gone from “literally… 1 per cent to “almost a thousand” councillors in under five years, relying almost entirely on the language of efficiency, promising to “cut wasteful government spending” and strip out regulatory “dither and delay.”

Birmingham, repeatedly cited as proof of Labour incompetence, was described as a city that could be “sorted, saved, and fixed by Reform”, though without any explanation as to how this would occur beyond the assertion that the Party would simply do better. Whether they actually would is debatable, considering other counties under Reform control in the Midlands, notably Warwickshire and Worcester, have not truly benefitted from Reform leadership. In fact, fiscal issues have arguably worsened.

Robert Jenrick

Immediately after, Robert Jenrick marked a shift from attempting to convince the masses with managerial rhetoric to decreeing Reform as the party of moral necessity. He implied his defection from the Conservative Party was the result of the Tory Shadow Cabinet being unwilling to admit that “Britain is broken”, recounting a meeting in which senior Conservatives rejected outright the phrase that has since become his war cry.

Further, he contrasted this with his own experience speaking to voters facing rising bills, stagnant wages, immigration pressures and failing public services, attempting to portray a dichotomy between how the Conservative Party views the state of Britain, compared to how the general public believe it to be. Reform, he suggested, is prepared to acknowledge the decline where other deny it, a framing that conveniently avoided any scrutiny of Jenrick’s own previous role in the governments that are now being held responsible for that decline.

Interestingly, Jenrick wasn’t attempting to appeal to Reformers, but instead, to current Conservatives, pleading with them to defect as he did. Loyalty to party, Jenrick argued, must give way to loyalty to country. He promised that Reform would “arrest our decline, stop the boats, secure our borders, raise living standards, fix our public services and restore pride.” The breadth of the ambition was striking, not least because it was delivered without reference to timelines, trade-offs or institutional constraints.

Speaking after the event to Jenrick, when asked about the emotional toll of defecting, the MP reaffirmed that leaving the Conservative Party had been difficult for him, but that fixing the country mattered more than party loyalty. Interesting, considering Reform believes loyalty to the movement to be core values for members.

Other Speakers

Lee Anderson followed, leaning fully into performative populism. Casting Reform members as the “people’s army”, he claimed that the majority had never previously belonged to a political party, presenting Reform less as an ideological project and more as an emotional outlet for accumulated frustration. His contribution relied heavily on ridicule and nicknames aimed at Labour figures, reinforcing the sense that Reform’s primary offer is cultural alignment rather than administrative competence.

After that, Andrew Rosindell described his move to Reform as liberation from a Conservative Party that had become overly managed and restrictive. Reform, he argued, allowed him to speak freely and honestly, likening the experience to “a bird being freed from a cage.”

Another Conservative defector, Danny Kruger attempted to supply Reform with institutional credibility, speaking of drafted legislation, civil service reform and readiness for government. He argued that the state had become obstructive, that intentional law had displaced parliamentary sovereignty, and that withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights was essential. It was the closest the rally came to administrative detail, though the solutions proposed relied more on confrontation with institutions than engagement with them.

Law and order dominated Sarah Pochin‘s intervention. Presenting herself as an outsider rather than a career politician, she promised an immediate national inquiry into grooming gangs and described the justice system as politicisied and failing victims. When asked whether a Reform government would act instantly, she replied, “Absolutely guarantee it”, a certainty delivered without any accompanying explanation of scope, legal process or parliamentary support. Although, Pochin did say how far elitism has penetrated politics, in particular, the fact that many MPs within Westminster come from “Cambridge, Oxford, Eton”, particularly ironic considering a majority of Reform MPs had attended private school, three of whom later went on to study at Oxbridge.

Suella Braverman completed the sequences by directing her criticism squarely at her former party. She accused the Conservatives of delusion, betrayal and cowardice, insisting they had never intended to leave the ECHR despite repeated promises. Drawing on her experience as Home Secretary, she argued that the convention had prevented deportations and undermined border control, presenting Reform as the only party with the resolve to act where others had failed.

And yet, Braverman remained a Conservative MP for almost two years prior to the Rwanda failure, despite Reform already growing in the polls at that point.

Nigel Farage

And then, at long last, it was time for the main event. Introduced by a barrage of pyrotechnics, Nigel Farage appeared on stage to a cacophony of cheers, once again appearing MAGA in nature. Farage’s keynote speech leaned heavily into cultural grievance, most notably in his outright dismissal of working from home, which he labelled “a load of nonsense.” He insisted that people are more productive when physically present with colleagues, framing remote work as symptomatic of a broader collapse in discipline rather than a response to technological or economic change.

This argument was less about productivity and more about signalling, positioning Reform against what Farage clearly views as a post-pandemic culture of flexibility, accommodation, and personal comfort. He then extended this line of attack by likening working from home to welfare dependency and what he described as an overtolerance of “mild anxiety”, arguing Britain requires an “attitudinal change” away from work-life balance and back towards hard work.

As with much of the rally, the point was not to offer policy, but to allocate blame, recasting structural economic issues as individual moral failure. It was an easy applause line, but one that reduced complex changes in how people work to little more than a lecture about character. A rather ironic one, considering that those in attendance clearly weren’t putting work first, as attending a rally at midday on a Monday isn’t something the majority of workers would be able to do. In fact, the only individuals truly working at the rally were the press, whom had been so cruelly ridiculed just hours before.

Following Farage’s keynote speech, a press conference was staged in front of the crowd, with journalists required to identify their outlet before asking questions, which lead to cheers from the crowd after GB News was introduced, and boos for the BBC. During the exchange, a reporter from the Daily Mirror asked about past comments made by Jenrick regarding demographic change in Birmingham, specifically whether integration should be by “the number of white people” in an area. Farage reframed the issue in terms of language and community before blaming “excessive levels of immigration” for social division. The press conference was brought to an abrupt end immediately afterwards, with no further questions taken.

Farage closed the rally by rejecting the charge that Reform remains a “one-man band”. Announcing that applications for general election candidates had opened earlier that afternoon, he declared the party on a “general election war footing” and promised the imminent unveiling of a shadow cabinet.

Rally Theatrics

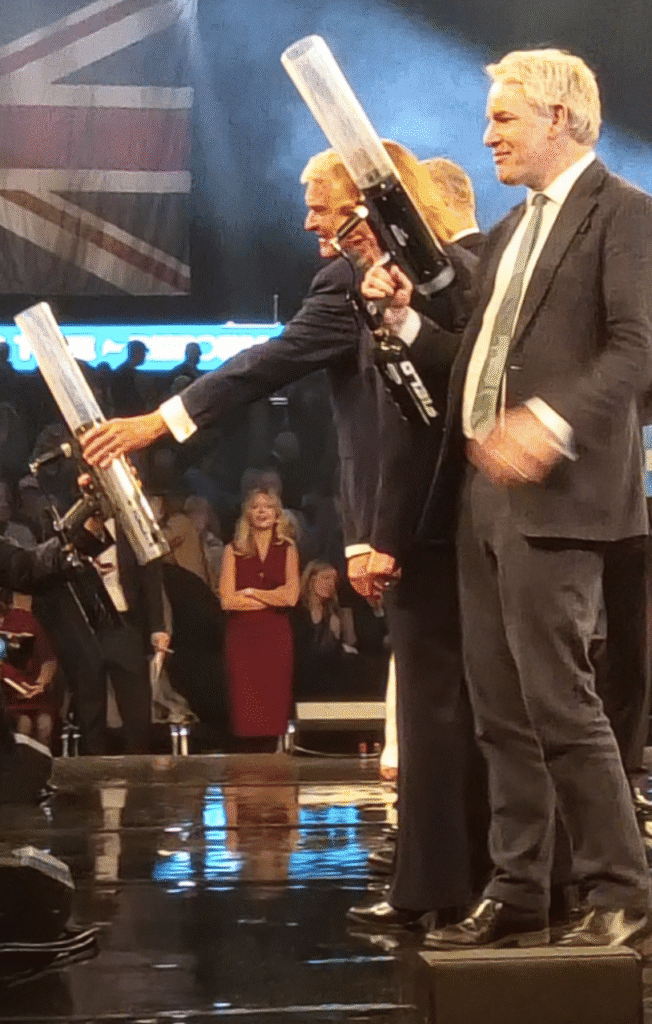

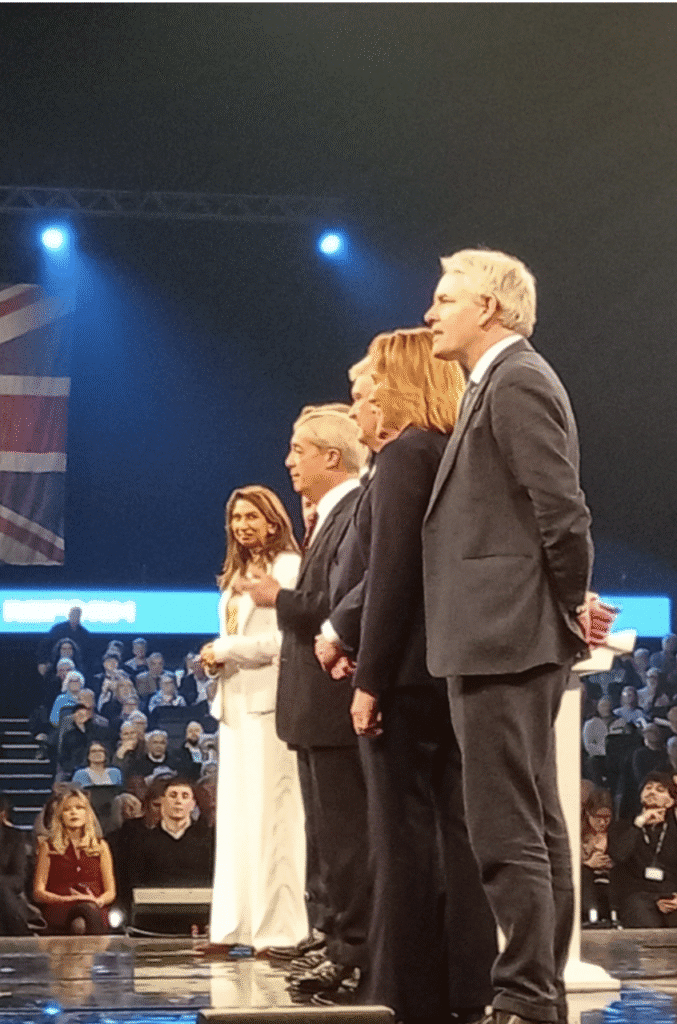

Finally, the parliamentary team was brought onto the stage together, presented as evidence of growing depth and seriousness, even as most of the substance remained deferred to a later date. After that, they decided to shoot Reform Football Club shirts into the crowd from t-shirt cannons.

The rally concluded much as it began: loudly, theatrically, and with confidence undimmed by contradiction. Reform UK left Birmingham presenting itself as a government-in-waiting, buoyed by spectacle, certainty, and the underlying assumption that acknowledging Britain’s problems is equivalent to having the solutions. Speaking after to Reform supporters and politicians, the atmosphere was obvious – Reform isn’t just political.

Reform has become the identity of some individuals, becoming the party of supposed morality, rather than solely policy. In reality, all the rally managed to prove is that Reform isn’t yet prepared to fix Britain’s broken systems. Perhaps decreeing the Conservatives as the party who broke Britain, whilst platforming former Conservative Party members as the future of Britain, doesn’t instil confidence in, blindside or convince voters.