The news that the Conservative Party was dead would be music to the ears of many in this country. Perhaps we’d see dancing and fireworks in the streets of northern England and Scotland, akin to what we saw when the news broke that Margaret Thatcher had passed. Labour activists might rejoice at finally being spared another tedious CLP meeting or the joyless ritual of being shouted at on doorsteps. Perhaps university students around the country would tear down the Che Guevara poster from their wall and declare victory. Temu and Etsy merchants would likely be lamenting the loss of their revenue when their “Santa Hates Tories” Christmas jumpers collect dust in a warehouse.

But the Conservative Party is not dead. It still wins elections. It still holds hundreds of seats. It currently sits in the driver’s seat of scrutinising the Labour government. But yet, in a deeper ideological sense, it may have died, or at least died a death in the sense that it abandoned the core principles that once defined it. For decades, the party has ceased to be a vessel for traditional conservatism. In its place is a politics of financial deregulation, global capital, and shallow cultural gestures. The values it once claimed to protect: community, moral order, intergenerational continuity, have been long abandoned in favour of asset-stripping, financialisation, and cultural grift. And in an ironic twist of history, those older instincts have found their most coherent defence not on the Tory benches, but in Labour; albeit awkwardly, within a faction of the party: Blue Labour. Emerging from the left, it is now arguably more conservative, in the traditional, Burkean sense, than the so-called Conservative Party itself.

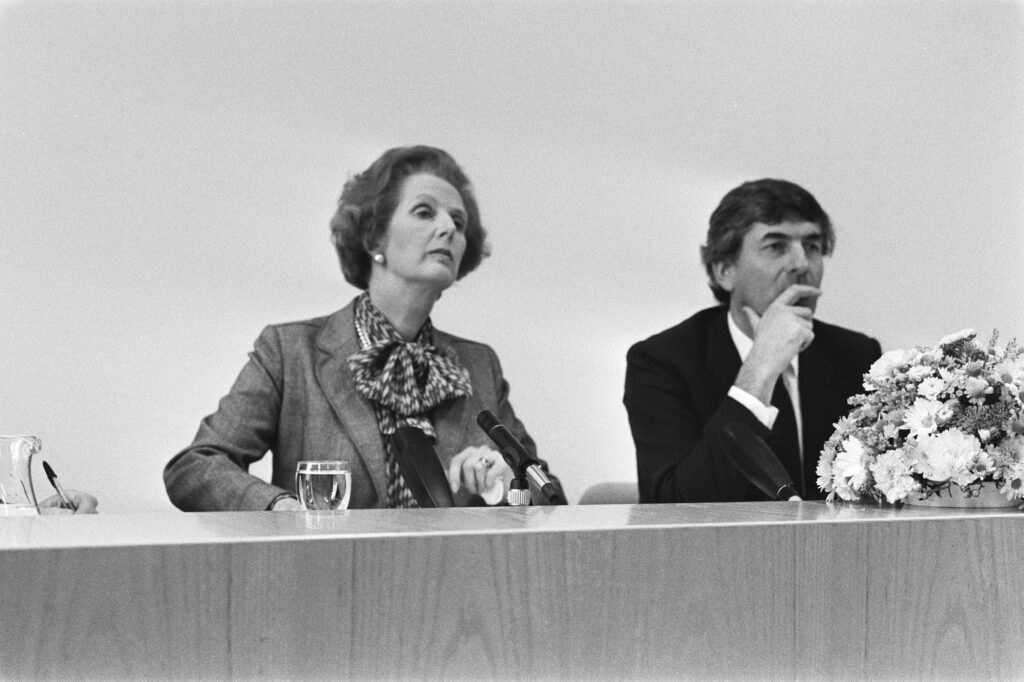

Of course, there was once a conservatism that conserved. It spoke in the cadences of duty and of continuity. It adorned itself in the modesty of cathedral towns, the quiet hierarchy of Rotary Clubs, the moral seriousness of Baldwin and Butskellism. It was suspicious of markets not hostile, but cautious. That world died in 1979. Or rather, it was deliberately dismantled, cheerfully sledgehammered by a grocer’s daughter from Grantham. Borrowing from the doctrine of Hayek, she turned conservatism inside out – gutting its moral impetus and replacing it with the cool, metallic logic of the market. Her ascent marked not just the arrival of Britain’s first female Prime Minister, but the dawn of a new decade. Defiant, cold and unapologetically neo-liberal, she ushered in an age where compassion gave way to competition, and the market reigned supreme. You wouldn’t be mistaken for sensing the entrepreneurial spirit in the air.

Since then, the Conservatives became rebranded as the “party of big business.” Where it once spoke the language of obligation and place, it now sang the praises of mobility, merit, and disruption. The ship of family values had sailed, and the vessels of asset bubbles and tax havens were already docking in the harbour. And without intending to, this transformation had unknowingly cleared the ideological ground for Blue Labour to settle into its new home.

By the time George Osborne was tweeting about “global Britain” from Davos, the transformation was complete. Conservatism had become the ideology of transnational capital with a Union Jack lapel pin. Where that matters is in the logic of policy itself. Industrial decline was naturalised. Mass immigration was depoliticised. Finance was celebrated as the highest form of national output. Conservatism had become not a worldview, but a set of Treasury spreadsheets dressed in tweed and the Blue Labour faction had stolen their clothes whilst they were bathing.

Blue Labour was not born in a think tank but in the rubble of moral and material decline. Emerging in the late 2000s under the intellectual guidance of Maurice Glasman, it was less a programme than an instinct, a recoil from the deracinated liberalism that left the electorate unable to get a cigarette paper between the New Labour and Tory successors.

Nowhere is the ideological bankruptcy of post-Thatcher conservatism more evident than in its handling of immigration. For all the talk of borders and sovereignty, the Conservatives and Labour alike became willing accomplices in the mass movement of labour. Rather than out of humanitarian generosity or liberal idealism, instead because it suited the interests of capital. But the social trade-off was the slow erosion of cultural cohesion, civic trust, and the familiar texture of British life. The promise was cheaper food and higher growth; what many got was a sense of being strangers in their own towns, overseen by a political class that insisted they were imagining things. On their journey to becoming the unwitting stewards of global capital, the Conservatives had done the opposite of conserve; they had ushered in a New Britain, one that looked different, sounded different, and was made legible only through the abstractions of GDP and diversity metrics. For a faction to emerge which captured the electorate’s wishes of a robust welfare state, strong communal ties and opposing mass immigration, it was tailor-made.

When John Lennon was notified of Elvis Presley’s death, he famously retorted, ‘Elvis died when he joined the army.’ What he meant, of course, was that Elvis’ real demise occurred with the end of the novel, rebellious era of which he emblematised, the moment he donned his combat uniform and buzzed hair; the quiet absorption into the establishment. Perhaps, similarly, the Conservatives didn’t die when they faced a crushing defeat to Starmer’s Labour in the summer of 2024, but rather when they flogged their linchpin principles of deference and moral duty in the unwavering pursuit of global capital.

Where Blue Labour most clearly embodies the lost soul of conservatism is in its emphasis on place, authority, and the moral economy. Maurice Glasman, its leading theorist, wrote not of revolutions or redistributions, but of communal relationships rooted in love, labour and power. He expressed his long-time interest in “MAGA” as “a strategy of coalition building in which workers can again have a voice,” given “the humiliation and degradation of the working class under the rule of the progressives.” This likely speaks to a divergence from Corbyn types and instead arguing for a politics grounded in obligation and the institutions of everyday life: the family, the parish, the workplace, the union branch – referring to progressivism as a ‘sickness, a palsy’. This is not the language of liberal progressivism or market libertarianism, but the language once spoken by Tory traditionalists like Oakeshott, Salisbury, or even Baldwin. It is wary of state overreach, but also deeply suspicious of unfettered markets. It insists that the bonds which hold society together are prior to both the state and the market—and that both should serve, not erode, those bonds. In this sense, Blue Labour has done what the Conservative Party abandoned in its Thatcherite turn: it has conserved something.