The First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) electoral system has been in use in the UK since 1884. This system tends to favour a concentration of votes rather than a more equitable distribution, resulting in a national two-party (or three-party) system, alongside some regional parties.

Generally, the FPTP system does not lead to intense competition or closely contested two-way races in each constituency and often results in majority governments. However, a shift from a two-party system to a three- or four-party system can create chaotic and unpredictable election outcomes, leading to ‘false’ supermajorities or ungovernable hung parliaments. This was evidenced by the 2024 UK general election, where Labour achieved a supermajority with only 34 per cent of the total votes.

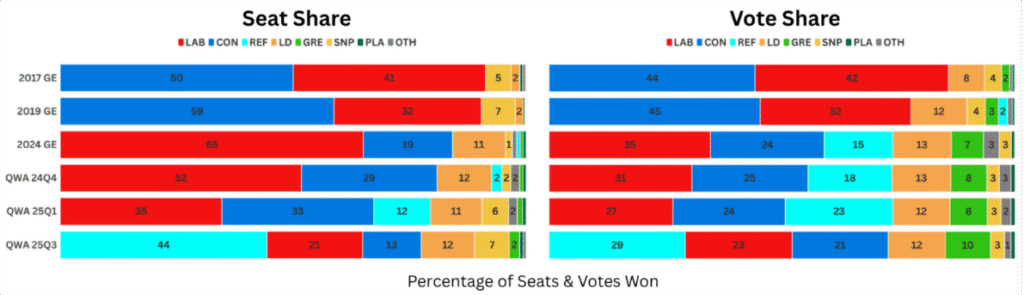

To understand the current state of FPTP in the UK, we have analysed the last three general elections, as well as Stats&Data Quarterly Westminster Assessments and Voting Intentions (24Q4, 25Q1, and 25Q3).

Below, we compare the percentage of seats and votes won during the last three elections, alongside our previous projections. During the 2017 and 2019 elections, the percentage of seats and votes won by the major parties was similar. However, in GE 2024 a significant disparity emerged: Labour secured 65 per cent of the seats despite receiving only 34 per cent of the votes, while other parties received a lower percentage of seats relative to their vote share.

Our projections for QWA 24Q4 and QWA 25Q1 indicated that both the Conservatives and Labour would receive a higher percentage of seats than their actual vote share. However, our latest QWA 25Q3 projections suggest that Reform is now expected to gain a higher percentage of seats than its vote share, while all other parties, except the SNP, are projected to receive a lower percentage of seats relative to their vote share.

Notably, a minor variation in vote share can result in significant changes in seat allocation. For instance, in our latest poll Reform’s vote share increased by 6 percentage points, but its projected number of seats rose dramatically from around 80 to 280. This creates a lottery-like system, in which different parties experience varying advantages and disadvantages at different times.

The graph below shows the average vote share required to win a constituency, alongside the margins of victory between the top three candidates.

The last main contest between Labour and the Conservatives took place in 2019. At that time, the average vote share needed to win was 54 per cent, suggesting that most MPs were elected with an absolute majority. Since then, the rise of parties such as Reform and the Greens, together with a growth in independent candidates, has reduced this average to around 36 per cent in our latest poll. This trend sits uneasily with the core principles of the FPTP electoral system.

In addition, the margins of victory between first and second place, and between first and third place, have narrowed sharply – from 25.8 per cent and 44.3 per cent in the 2019 election to roughly 8.4 per cent and 17.1 per cent in our latest projections. This decline indicates growing competitiveness in both two-way and three-way contests, as illustrated in the second graph.

Alternative electoral systems to First-Past-the-Post

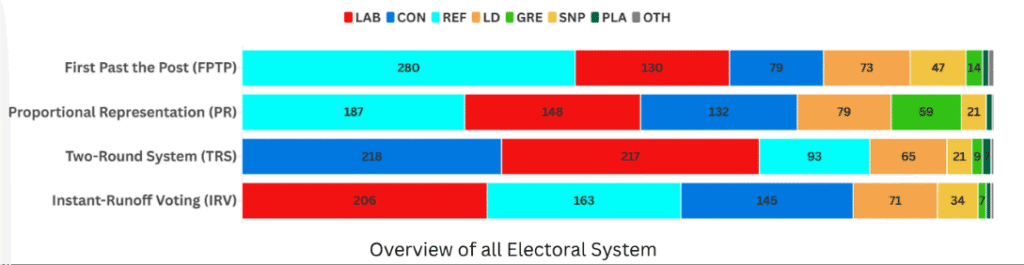

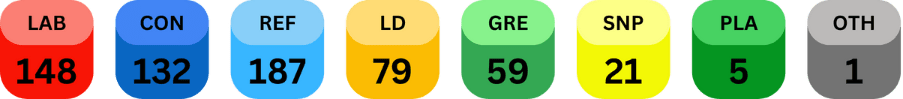

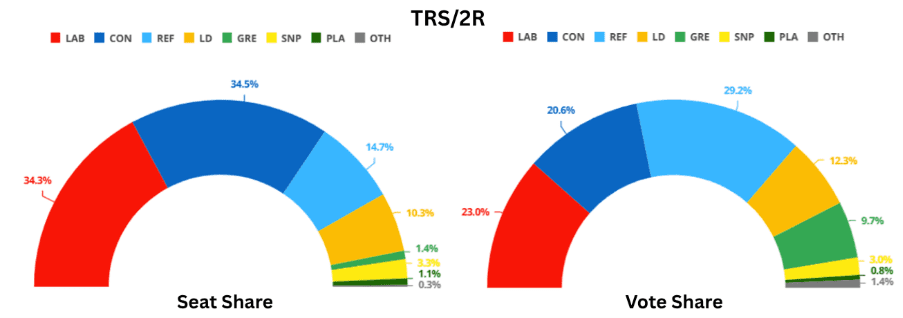

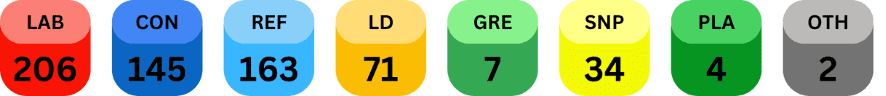

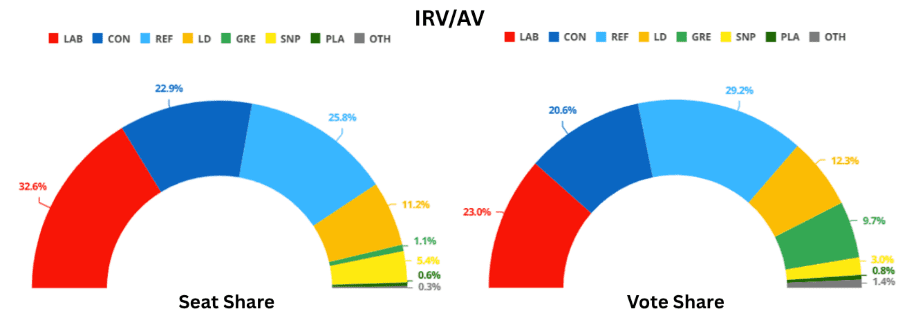

All projections for the alternative electoral systems are based on our latest Quarterly Westminster Assessments and Voting Intentions for 25Q3. The projected seat shares and vote shares are set out below for reference.

1. Proportional representation

The Proportional Representation (PR) system allocates seats to each party in line with its overall share of the vote. Constituencies may be represented by multiple members, and a minimum threshold can be applied nationwide to prevent regional parties from being disadvantaged. This system emphasises the overall distribution of votes rather than their concentration in particular areas. As a result, it is often difficult for a single party to secure an outright majority, and coalition governments become the norm. This is evident in countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands, where elections are held under PR and the current governing coalitions each comprise five parties.

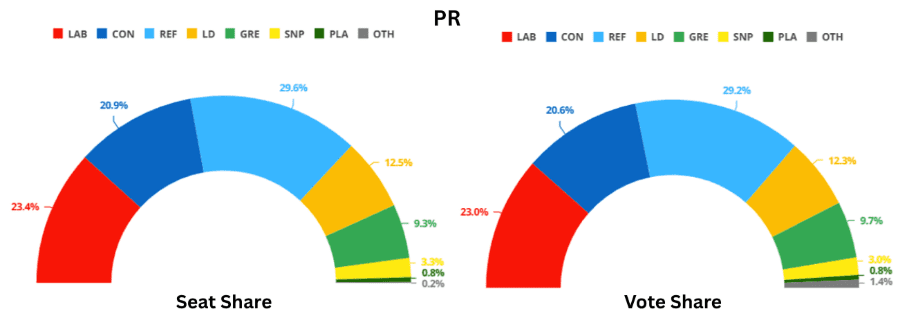

For our analysis, we have divided the UK into four parts – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – to allow for the representation of regional parties. We have also applied a five per cent threshold to limit the influence of very small parties.

Compared with our FPTP projections, we expect both Reform and the SNP to see a significant reduction in seats, while the Greens and the Conservatives gain ground. This outcome would almost certainly require a coalition of three or more parties to form a stable government. The main advantage of this scenario is that the percentage of seats won closely matches the percentage of votes received.

2. Two round system

The Two-Round System (TRS) is a single-winner electoral system designed to ensure that the elected candidate has the support of a majority of voters. It consists of two rounds of voting. In the first round, voting takes place under FPTP. The two candidates who receive the most votes then progress to a second round. If any candidate receives more than 50 per cent of the votes in the first round, a second round is not required.

France uses a similar system for electing its parliament. One key advantage of this model over FPTP is that each MP is elected with an absolute majority. In addition, the system tends to favour centrist parties over more extreme ones, as it encourages voters to make choices along ideological lines in the second round, which in turn leads to more tactical voting.

If elections were conducted using this system, both the Conservatives and Labour would be expected to gain significantly at the expense of Reform, the Greens and the SNP. As noted above, the system promotes tactical voting, which helps limit the influence of more extreme parties. For example, in second-round contests between Reform and the Conservatives, voters from other parties are likely to consolidate behind the Conservatives, even if Reform is ahead in the first round. A similar pattern would be expected in contests between Labour and the Greens. Most other second-round match-ups would be shaped by broad ideological divisions.

3. Instant-runoff voting or alternative vote

Instant-runoff voting (IRV) is a ranked voting system used to elect a single winner. It simulates multiple run-off elections through a series of eliminations. In each round, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed according to the next preferences indicated on the ballot papers. This process continues until only one candidate remains, who is then declared the winner. Australia has used IRV for many years.

In our analysis, if elections were conducted under this system, the results would broadly resemble those produced by the Two-Round System (TRS), as both are based on similar underlying principles. The main difference is that Reform tends to perform better in constituencies where it competes against the Conservatives. This occurs because left-of-centre votes transfer to Labour, allowing Labour to overtake the Conservatives before the final stage. The final contest therefore becomes a run-off between Labour and Reform, with Reform winning the seat rather than the Conservatives.

Conclusion

We have examined three alternatives to FPTP. Each produces different outcomes in terms of which party (or parties) governs and the likelihood of a hung parliament, underlining the complexity of British politics. However, all three offer more representative outcomes than FPTP and reduce the scope for highly unpredictable results.