After the Fire at Tai Po, Hong Kongers demand answers. But the government cracks down on dissent harder than ever.

Throughout Saturday and Sunday, Tai Po became a sea of flowers. Thousands queued along the riverbank leading up to the burnt-out ruins of Wang Fuk Court, where a fire had left 156 dead as of Tuesday. People stood in line for hours to lay white flowers in front of the buildings. Many of the mourners were crying, shaking their heads in disbelief as they looked up towards the blackened towers. But besides the grief, another feeling was palpable: anger.

Image: Mourners queue to lay down flowers the site of the blaze

An Avoidable Disaster, Years in the Making

As the scope of the tragedy grew clearer, so did the questions over whether it could have been prevented. The Labour Department, responsible for construction safety, had confirmed over the weekend that it had been receiving fire safety complaints from residents of the estate about construction mesh and scaffolding around their buildings since last year. The department had reportedly inspected the site several times, most recently on the 20th of November, issuing warnings to the contractor, but never enforcing them.

Local media also reported that Tai Po district councillor Peggy Wong acted as a consultant to the company managing the renovations, though Wong denies involvement. On Monday, city officials stated they found mesh at the site that did not meet fire safety standards. Hong Kong police subsequently arrested 13 people connected to the construction firm.

The government has accused the firm of “gross negligence.” City leader John Lee stressed that police will find the culprits and announced an “independent review committee” chaired by a judge. Lee acknowledged the need for “systemic” reform, admitting there had been “several lapses.”

But many aren’t convinced the government will actually get to the bottom of this.

“It’s ridiculous”, said Janet Chung, as she queued to lay down flowers at the site of the fire. Chung, who asked to use a pseudonym, had been there every day since the fire started on Wednesday. “Police arrested the first of the 13 a few hours after the towers started burning,” Chung said. “How on earth did they investigate anything that fast?” She was also angry at Chief Secretary Eric Chan saying the city would phase out bamboo scaffolding as a result of the fire. “Bamboo isn’t the cause. It’s corruption,” she said, lowering her voice. People in the queue started to turn around. Criticising the government has become dangerous in Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong people understand this was not an isolated incident,” said Kris Cheng, a journalist from Hong Kong now based in the UK, who has covered the city for years. “There are systemic issues: the failure to eradicate corruption in the bidding process for construction building, the hiring of external labour to cut costs, and the use of poor-quality materials.” Cheng notes these problems have been known for years. “Ironically, some of the people who raised these issues are now in prison for their political activities,” he added.

The Arrest of Miles Kwan

Miles Kwan hands his leaflets to anyone who wants them. On this Friday night, two days after the fire started, he positioned himself strategically at the main exit of the busy Tai Po Metro station as commuters rushed by him. “We Hong Kongers are united in grief, united in anger about this fire”, Kwan told local media outlet Hong Kong Free Press. On the leaflets, he had written four demands to the government, calling for an independent inquiry into the cause of the fire and holding officials accountable. “If the government interprets these simple demands as inciting hatred, that would be very oversensitive of them”, Kwan said.

Amidst the anger, Kwan’s demands for accountability hit the nail on the head for many Hong Kongers. A petition started by the student online reached 10,000 signatures within a day, as thousands voiced support on social media. Then, on Saturday evening, the petition disappeared. Local outlet South China Morning Post reported that Kwan had been arrested for sedition, which carries a penalty of up to 10 years in jail under new security laws. On Monday, Kwan was photographed leaving a police station.

After Kwan, two more people were arrested for sedition, including a former pro-democracy district councillor. In a press conference, city leader John Lee did not comment on individual cases, but said that most Hong Kongers stood together in the face of the fire. “But we will show no tolerance for those who disrupt this unity now, who exploit this tragedy,” Lee said. Similarly, Beijing’s national security office in Hong Kong has warned “anti-China disruptors” that they will face the “full force” of the security law. Chinese State newspaper “China Daily” directly referenced Kwan’s petition in an editorial on the weekend, speaking of actors allegedly attempting to “tear society apart under the guise of petitioning.”

People lay down white flowers in front of the burnt-out towers as part of a temporary vigil in memory of the 156 people that were killed in the fire

Behind the Crackdown

“This said a lot about shrinking room for freedom of expression in Hong Kong,” said Alan Tan. A well-known political commentator who remains based in Hong Kong, Tan did not want to be identified by his real name. “What they are most scared of is that Kwan called for an independent investigation. The government is paranoid of a commission that could summon their own officials.”

The commission launched by John Lee will not have those powers. It cannot summon officials or punish them for refusing to answer questions. Although Lee acknowledged the need for systemic reform in Monday’s speech, he said the investigative review would be sufficient.

Kris Cheng said Kwan’s arrest did not surprise him. “These arrests create a climate of fear,” he said. “That is exactly what the government wants. People are allowed to be sad, but they cannot be angry publicly.” Yet he argues that Hong Kongers are angry. “The fire was likely preventable, yet under the current system, those brave enough to speak out end up behind bars. That is what makes people the angriest.”

Cheng points out that the swift crackdown likely occurred because Kwan’s “four demands” reminded authorities of the “five demands” at the center of anti-government protests that rocked the city in 2019. “They are very sensitive about that topic,” Cheng said.

Hong Kongers staged mass pro-democracy protests in 2019 and 2020, which turned increasingly violent on both sides and ultimately culminated in a government victory and the passage of the National Security Law, which protesters had warned would be a tool to silence dissent. After a crackdown on civil society and democratic backsliding facilitated by then-security minister John Lee, a mass exodus of pro-democracy Hong Kongers followed. Now that Lee is city leader, observers say he has further cracked down on freedom of speech. Lee himself maintains Hong Kongers can still express their opinions freely, and that the National Security Law merely protects the peace, while he is leading Hong Kong into “order and prosperity” in strong collaboration with mainland China.

Tight Control- Inspired by the Mainland

“In Hong Kong, we’re seeing a very Chinese approach of crushing all dissent by force now,” said Emma Smith, a financial professional who witnessed the 2019 pro-democracy protests first-hand. She did not want to be quoted with her real name. “At least, because Hong Kongers still have some guaranteed rights under the Basic Law, [the government] need the workaround of the vague national security law. But that works fine for stomping people’s rights,” she said.

Kris Cheng agreed, “officials in Hong Kong now routinely echo Beijing’s rhetoric and prioritise ‘stability maintenance’ over transparency. This is very much the Chinese model.”

For Cheng, the intensity of the Hong Kong crackdown also reflects lessons Beijing has drawn from its own protest movements. He points to the 2022 White Paper Movement, where young people took to the streets holding up white sheets of paper. It remains the most open challenge to Xi Jinping’s rule in recent years. “And it all started with a mishandled fire in an apartment block in the city of Ürumqi,” Cheng said. “So the Chinese government knows what something like this can ignite.”

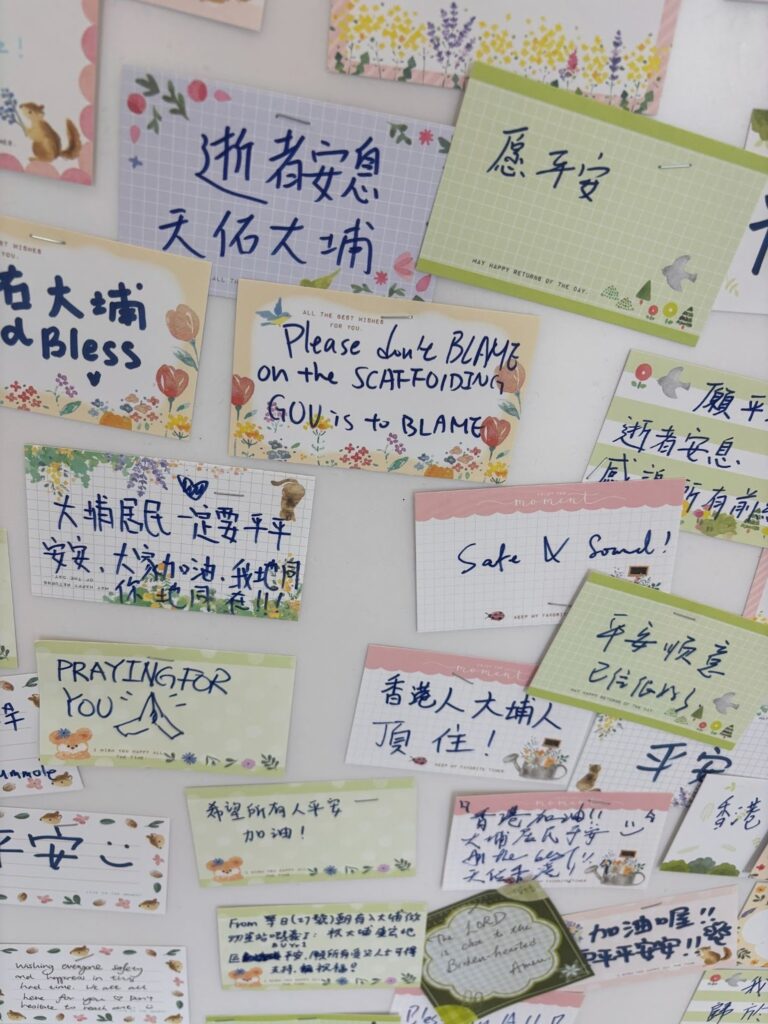

Image: “GOV is to blame” message on a Lennon Wall

Echoes of a Different Time

Indeed, it became evident that despite the fear, the government cannot quite stifle a certain rallying spirit. Around the city, “Lennon walls”, styrofoam boards where people attach post-its, appeared again. A method used in 2019 to voice anonymous dissent, several walls now contain defiant messages about the fire.

And, like in 2019, volunteers around the site of the fire gathered quickly, without being told to, organising help and supplies for both victims and first responders via social media, bridging the city’s diverse communities. “This is the Hong Kong spirit,” said Faisal, an imam at a mosque near Tai Po. He had shown up at the site of the fire for the third time on Sunday, bringing Pakistani food for the displaced. “Everyone helps together here, no matter where you’re from,” Faisal said proudly. “We don’t need a leader for that.”

Image: Election posters in Wang Fuk Court

An Election Few Expect Much From

Around Wang Fuk Court, election posters still hang. The vote for Hong Kong’s Legislative Council will go ahead on December 7. But the political system has been dramatically reshaped. After a sweeping overhaul, the public elects fewer representatives, and all candidates must be vetted by a committee to ensure only “patriots” govern.

“It will not be an enthusiastic event,” said Tan. The previous election under the new system drew a record-low turnout. This time, despite free public transport and celebrity advertisements, Tan predicted apathy. “The future of democratic development is bleak.”

Cheng agreed: “The fire gives them an excuse for a potentially low turnout at least. They will try to pretend everything has gone back to normal after.”

Image: Mourners queue along the Tai Po riverbank, watched by police

Back in Tai Po, the election feels far away. Janet Chung laughs bitterly at its mention. “When is that even? They have to have it, I guess.” Chung has made it to the front of the line, the square underneath the towers. Swarming with volunteers days ago, it is now staffed with government employees. “Go, go,” the staff hurry mourners along. After standing in the queue for over an hour, they get twenty seconds to lay down their flowers before being ushered back towards the station. The mourners have been allowed a bit of sadness. Nothing more.