They arrived at the Reform Conference with the air of revolutionaries, though their revolution seemed less “storm the Bastille” and more storm the parish council’s budget line for bunting. Reform’s emphasis on selecting young people for council seats has been a blatant attempt at branding itself as a forward-thinking bastion of modernity, although on the surface it takes the form of interns being wheeled out to show the party isn’t entirely made up of golf-club pensioners and ex-UKIP defectors. George Finch, just 19, became permanent leader of Warwickshire County Council this year; overseeing a council serving roughly 600,000 people, managing a £500 million budget and managing services like children’s social care and corporate parenting. Charles Pugsley, also 19, cabinet member for Children’s and Family Services at Leicestershire County Council—juggles uni responsibilities alongside running critical public service delivery.

Naturally, the youth in positions of managerial authority habitually sparked a knee-jerk reaction of panic and dismay. Finch’s supposed local counterpart, Warwickshire’s Labour MP, Matt Western, warned that placing an 18-year-old in charge of a £500 million budget risks chaos and sows instability across essential services. When scrutinised on his age and its effect on his important role, Finch spoke in all of the self-assured, clipped and rehearsed confidence of a sure-fire professional, although it emanated a feeling of costume rather than genuine conviction.

However, Reform’s focus on nominating itself as the poster boy of youth dynamism is not something particularly new in politics. Reform – a party associated with the sepia tones of the past, the pint-at-noon patriot, the eternal chorus of ‘it wasn’t like this in my day’ – now seeks to cloak itself in a Dionysian, fresh-faced linen whilst simultaneously railing against anything that faintly smells of modernity. Almost identically, Blair in the 90s tried to embody an oxymoronical twist of being pictured with Oasis, drinking pints with rolled up shirtsleeves, whilst also never being able to shake the Oxford graduate, Middle England pneuma in which he was immaculately cladded in.

When Margaret Thatcher boasted that her proudest offspring was in fact Tony Blair, what she meant was that his ascension marked the end of the expected trope that donning a red rosette automatically marked a progressive future and signalled the end of the hopeful contradiction that youthful radicalism and centrist managerialism could live together in harmony. Perhaps that is the source of our confusion when we see fresh-faced teenagers in suits and lanyards representing parties associated with bygone days where regressive attitudes were the status quo. In this light, the allegations of age and lack of professional experience being a disruptor of effective leadership is just a convenient excuse to help us in our confused viewing of seeing polished, equine prefects parroting the reactionary doctrine of Nigel Farage.

Although not a councillor, 12-year-old party member Aidan Barrett spoke proudly of his age and his unyielding hope in Farage to “save this nation.” Citing the reason for his home-schooling, the ‘L-word’ soon followed. “LGBTQ agendas…” he rasped, “are being pushed onto children” in formal education and the fear of mentioning “Winston Churchill.” Perhaps it is here where we see the contradiction in its most visceral, loudest form. An eerie spectacle of children speaking not with the unvarnished energy of youth, but in the hand-me-downs of adult conservative yearning.

Ultimately, Reform’s Young Councillors are not the shock troops of tomorrow, but rather the meticulously packaged echoes of yesterday, carrying reactionary daydreaming in the most unlikely vessels – schoolchildren, students, and 19-year-old council leaders. Although as established, not a novel phenomenon, Reform’s Young Councillors reveal the end of the great illusion that youth naturally signifies progress or insurgency. Instead, we see the trappings of youth in suits, lanyards, Twitter-ready confidence and the idea that this can cleverly mask the old order and turn the promise of rebellion into its own reproduction. Don McLean’s ‘American Pie’ lamented the day “music died” when a plane crash killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson. The death he was referring to was not music, but rather the youthful optimism and revolutionary spirit creeping its way into 1950s America, of which the crash delivered its final blow. Perhaps this speaks to our dismay at the young councillors as a symbolic “death of youthful rebellion” – their radical potential has been co-opted or hollowed out for adult grievances they didn’t author.

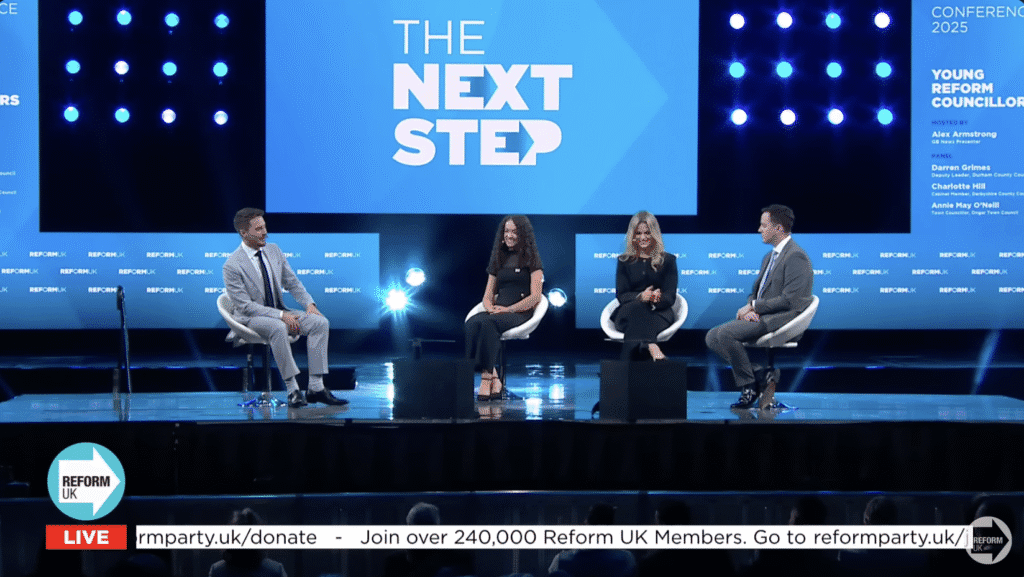

Featured image via Reform UK on Youtube